Jane Badger Books

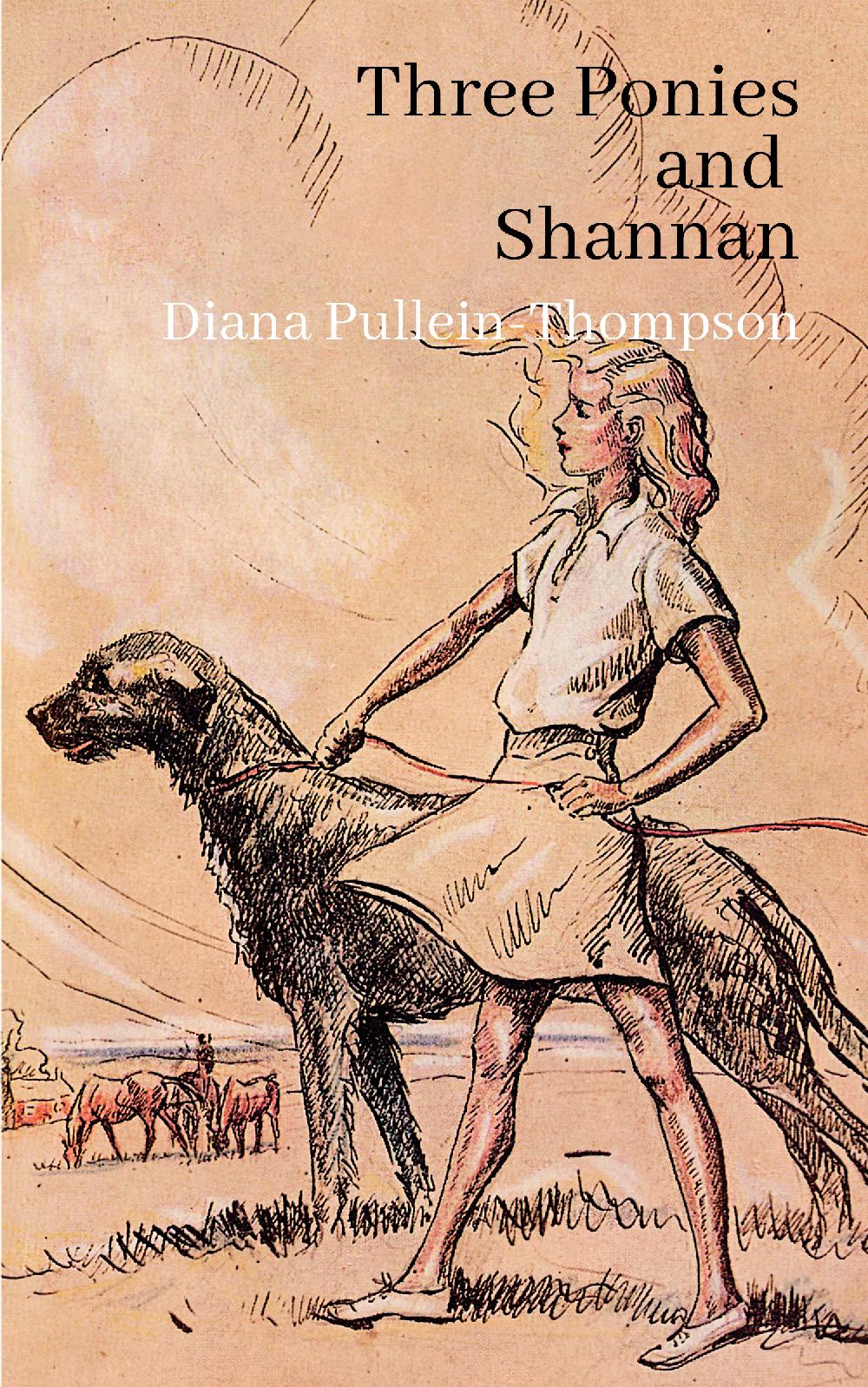

Diana Pullein-Thompson: Three Ponies and Shannan (paperback)

Diana Pullein-Thompson: Three Ponies and Shannan (paperback)

Illustrator: Anne Bullen

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Diana Pullein-Thompson’s classic 1940s pony story looks at the poor-but-noble heroine and the rich-girl-villain, and turns the stereotypes on their heads.Christina has everything – beautiful ponies, a lovely house, and a groom to look after her beautiful ponies. But Christina has just moved into the lovely house, and the family that lived there before didn’t want to leave. Christina has no friends, and her attempts to make some go disastrously wrong. Together with her Irish wolfhound, Shannan, Christina then goes to a local riding camp, and life changes.

Fully illustrated edition with all the beautiful original illustrations by Anne Bullen.

Augusta and Christina series 2

Page length: 208

Original publication date: 1947

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

The Horse Show was over. I stood in the shade of a chestnut tree and watched my three ponies led up the ramp into the horse-box, one by one.

Symphony went first. Her chestnut neck shone in the dwindling sunshine. Her checked fly-sheet and blue bandages appeared gay and dashing. On her head-collar O’Neil had tied her red rosette; it looked lovely against her golden forehead and beside the dazzling white of her star.

Second went Solo. He walked with short, jaunty steps, his little docked tail carried high, his eyes rolling and showing their whites. He, too, wore a fly-sheet and bandages, but they did not suit his dark brown coat and black points like the gold of Symphony’s; somehow they lost their gay effect.

Last walked Serenade. His bay ears were cocked forward. His brown eyes were shining. He seemed pleased to be going home after the heat and bustle of the long day. I noticed that one of his seven neat plaits was coming unsewn and mud clung to his bandages, which he had worn while jumping in the ring. His rosette was not tied to his head-collar and I supposed that O’Neil thought that red did not suit his bay coat.

When all the ponies were in the horse-box, the ramp was put up and I turned and walked away to find my parents. The Show Ground was emptying fast. The entrance was crowded with ponies and children, many of them carrying knapsacks. I had to wend my way amongst them to the car park and I felt as though all their eyes were upon me; it was not a pleasant feeling, because I knew that I had spoiled the horse show for most of these local competitors. I knew that they must have spent ages practising their ponies and preparing for it, have risen early to plait manes and wash tails, and I was certain that they resented me competing. They thought it unfair that a newcomer should bring three prize-winning ponies and a groom in a horse-box and carry off all the prizes.

Now, while I walked, my mind drifted back to the morning. I remembered how, after Symphony and I had won the Showing Class and Best Rider Cup so easily, while O’Neil took hold of my reins I heard two girls talking. “Look at her,” one had said, “just chucking her reins to a groom. I bet she just thinks of her ponies as winning-machines and sells them when they get old.” “She probably doesn’t even know how to put a bridle on. I expect the groom does everything,” said the other girl.

Later, when Serenade was leading the way round the ring after winning the Jumping Class, I heard some onlooker—a man, by his voice—remark, “It’s disgusting that professionals like her should be allowed to come here on trained jumpers and take all the prizes away from the local children.” I had felt angry then and told my father, and he had told me not to pay any attention to such jealous, spiteful people. But afterwards, when I had won all but one gymkhana event on game little Solo, I began to feel guilty, especially when I saw a red-headed boy patting a little black pony, which I had just defeated in the Bending Race, and heard him say, “Never mind, Sootie, you can’t expect to beat these hundred-pound ponies, who live on oats and go everywhere by box.”

The worst of these spiteful remarks was that some of them were true. Solo had cost a hundred guineas and I had handed my reins to a groom. I realised too, with a pang of anger, that I could not adjust a double bridle properly, and that probably these local children knew more about horsemanship than me. I had won at all the biggest shows in England and now I began to wonder whether it was really money and not riding that had been the cause of my success. Suddenly, for the first time in my life, I wished that I was poor, that my parents

would not buy me almost everything I wanted. I was beginning to imagine myself like the other children—with straight hair instead of the little neat curls my mother liked—when I found myself at the door of our car with my parents’ eyes upon me.

“Hallo,” I said.

“Well,” said Daddy, “you seem to have carried off most of the prizes to-day.”

“Solo was really splendid,” added Mummy.

“Yes, he was,” I said, getting into the car.

“Cheer up, Christina, you look tired,” said Daddy, starting the engine.

“Have a sandwich,” said Mummy.

“No, thanks. I’m only hot,” I said.

The car glided forward and we purred through the car park. As we drove through the entrance of the Show Ground, I saw a girl with fair hair nudge a boy wearing spectacles and then point at me, and I felt like a criminal.

“Daddy,” I said, “do you mind if I hack to the next nearby show instead of boxing?”

“My dear child, whatever do you want to do that for?” he said.

“What a silly idea,” remarked Mummy. “You’ll only get overtired.”

“All the other children do, and they don’t get tired, and it seems unfair for me to go to these small shows in a box,” I said.

My parents looked at one another. “Well, we’ll see when the time comes,” said Daddy.

We drove on in silence and every now and then we passed some of my fellow-competitors. They all seemed to see me and I wished that I was riding home, too, instead of lazily lounging in a car, leaving my ponies to be cared for by a groom.

Soon the silence was broken by Daddy pointing out that I had won my twenty-first cup. I said that it wasn’t me who deserved it, but Symphony or the man who trained her. Mummy said that I was talking nonsense and had ridden splendidly. Just then we passed a freckled girl and red-headed boy on a hill. They were leading their ponies and eating chocolate biscuits, and they had taken off their coats and thrown them across their saddles.

They were wearing short-sleeved yellow shirts, and the girl’s jodhpurs were too small and the boy’s too big, but all the same they looked very sporting.

“What a scraggy pair of children and ponies. They both look as though they need O’Neil and the clippers after them,” said Daddy.

“I think they look rather nice,” I said.

A little later we drove up the long drive and drew to a standstill outside the beautiful Regency house that Daddy had bought a month before. We stepped out of the car and the white door was opened by Walters, the butler. Mummy showed him the cup that I had won and he took a respectful interest, and then she told me to hurry and have a bath and change for dinner. I dashed up the broad staircase, along the light passage to my lofty bedroom.

While I lay in my bath I imagined the other children’s home-comings. I guessed the freckled girl and red-headed boy were brother and sister and I saw them leading their ponies into an old low-roofed stable. I thought of them filling two hay-nets and spreading straw in the looseboxes. Then I saw them walking down a winding path thick with weeds to an ivy-smothered house, and I guessed they would be talking about the lazy, rich girl, who glided home in a car to lie in a marble bath before eating a four-course dinner, waited upon by a wooden faced butler. When I had got this far, my daydreams were interrupted by Mummy tapping at the door and telling me to hurry.

After dinner I collected several lumps of sugar and went to see my ponies. Serenade was lying down, and he blinked when I turned on the electric light. He looked awfully sweet and I sat down beside him and gave him two lumps of sugar and patted his sleek, bay neck and scratched his little white star.

Solo was standing with his back turned to the loose-box door, as though he was in a stall. He seemed pleased to see me and gobbled the sugar, but he was as nervous as ever and when I raised a hand to brush a fly from his forehead he jumped out of my reach. I told him that he was a silly fellow, and wondered whether O’Neil ever hit him. Then I walked on to see Symphony. She was looking out over her door, but when she saw me she laid back her ears and turned away, and I had to go into the box to give her the remaining sugar. I patted her for a few minutes and thanked her for being so good in the Showing Class. Then I bade her good-night and went indoors.

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans: Augusta Thorndyke, Christina Carr, Mrs Thorndyke, Charlie Dewhurst, Heather and Pat, Madame Dupont, O'Neil, Phyllis, Eleanor Langford, Mike, Terence, Nigel, Piers, Tilly,

Equines: Daybreak, Solo, Serenade, Symphony, Swallow, Amber, Sootie, Nightmare, Harkaway, Seaspray, Jingle, Punch

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order

1. I Wanted a Pony

2. Three Ponies and Shannan

3. A Pony to School

4. Only a Pony