Jane Badger Books

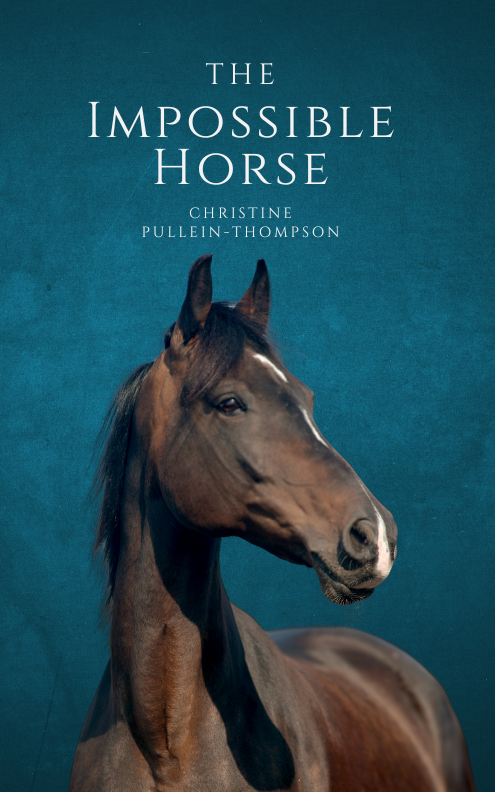

Christine Pullein-Thompson: The Impossible Horse (paperback)

Christine Pullein-Thompson: The Impossible Horse (paperback)

Illustrator:

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Can Jan prove to everyone that Benedictine, condemned as a dangerous rearer, is not an impossible horse? And can she prove to Guy that she is not just a horsy girl who always has straw in her hair?

Jan goes to her first hunt ball, finds her way in her new career schooling horses, and edges closer to a relationship with Guy

First published in the 1950s, this book was written when hunting was legal. There is a lot of hunting in this book, and an upsetting scene of animal death. For that reason, we recommend this as a read for over 18s only.

This book is not illustrated.

Page length:

Original publication date: 1957

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

I SUPPOSE last winter was one of the most eventful in my life. Everything began on a wet December day with an east wind which cut through you like a knife, and a sky which promised nothing but more rain.

It was hardly a day for hunting, but hounds were meeting at Little Cross and nearly everyone would be there—by that I mean all the local people, Chris Miller, Guy Maunder, the Stanmore girls and their mother and a host of younger children and a collection of adults whom I knew by sight, but not by name, and, of course, the Master, Captain Williams.

I was seventeen and had just left school. As an experiment I was taking horses to break and school and at that time I had three in my stable, grey Fantasy, piebald Domino and an ugly black called Velveteen. I lived with my parents in a plain stone Victorian house with a gable at each end, and old-fashioned stabling for four and a paddock.

On that morning, I rose early and lunged Fantasy before starting to groom Velveteen, whom I had decided to hunt. I remember his temper was even worse than usual and I wondered whether he would ever improve and be suitable for his owner, a woman called Miss Presscott.

The weather-cock above the stable pointed east when I hurried indoors for breakfast. Mummy was up and had put the kettle on. She and I are not very alike; she is small and dark with lovely hazel eyes, while I’m five foot eight and have flaxen hair. Often I wish I was smaller, so that I could school ponies; as it is, I can’t take anything under fourteen two.

We made toast together, before Daddy appeared in a dressing-gown and said, “You’re hunting today, aren’t you, Jan? Be careful. The forecast says snow.”

I said, “Okay. I shan’t stay out too long. I’m taking Velveteen, and he isn’t very fit.”

Daddy is half Swede and has a great deal of hair, which in certain lights looks nearly white. He was invalided out of the Navy after the war with a wonky leg.

“Is that the horrid black?” asked Mummy.

“Yes, but he’s much nicer now,” I replied before I dashed upstairs with a piece of toast in one hand and a mug of coffee in the other.

I changed quickly. I hadn’t any hunting clothes and I put on jodhs, a polo-necked jumper, socks, shoes and a dark hacking jacket. My hat and hunting whip were in the hall. Mummy had made me cheese sandwiches. She kissed me.

“Do be careful,” she said.

Outside sleet was falling. I thought of turning back for my mackintosh, but I hate hunting in one and there would be no one to take it from me at the meet. So I went on without it and fetched an eggbutt snaffle and a saddle from the tack-room and put them on Velveteen. He nearly bit me as I pulled up the girth, and his ears were back as I led him into the small Staffordshire-bricked yard.

Mummy called “Don’t stay out too long” from an upstairs window as I rode out of the yard and Daddy opened the back door and called, “Have a good day.”

The road to Little Cross looked bleak and cold and Velveteen jogged and threw his head from side to side. And now the sleet was falling in earnest and I wished that I had brought a spare pair of gloves.

The fields around us are open and fenced by cut and laid hedges and occasionally wire. But as you near Little Cross the landscape changes and there are friendly hills, beech woods, a winding river and thatched cottages. When I came to the first wood, Velveteen seemed to settle down and there was shelter from the sleet and we both began to feel more cheerful. And presently I heard the sound of hoofs behind and hounds came round the corner gay and smiling. Tom the huntsman called, “Good morning, missy. What weather!” And somehow the scarlet coats, the jingling bits, the creak of leather seemed to dispel the bleakness of the day, and I felt like singing as we all rode on along the road together.

“What have you got today?” Tom asked.

“Miss Presscott’s black. He’s called Velveteen.”

“Looks up to plenty of weight,” said Tom.

The Stanmore girls were already at Little Cross when we arrived. Audrey, the eldest, was mounting a chestnut with three white socks, Susan was on her usual roan, and Sonia the youngest was patting a big bay which they had just bought from Miss Peel.

Miss Peel runs the local riding school and dealing establishment. She is small and wiry and one of those ageless people who might be thirty, or forty, or even fifty. She is a very good instructor and works from dawn to dark without ever seeming to make much money. She taught me most of what I know about riding.

Now Sonia was trying to mount the bay, and he was twirling all ways and banging her behind with his head. Tom, who dislikes the Stanmores, said, “Look at her. Can’t even mount her horse,” and laughed scornfully.

The Stanmores’ groom stepped forward then and held the bay. At the same moment I saw Guy Maunder arrive with his car and trailer.

Guy is dark with brown eyes. He was eighteen then and on leave from his National Service. He is the only son of the local M.P. I’ve known him since we both started riding at Miss Peel’s and I had a pash on him when I was twelve. I still found him attractive and sometimes I would imagine us dining by candle light or spending a long dreamy day together on the river. But probably, because I admired him and because he was very popular in the neighbourhood, I never really expected it to happen.

Now he saw me and called, “Hullo, Jan. New horse?”

I said, “Miss Presscott’s Velveteen. I’m schooling him.”

And he said, “Is he nice?” while he unboxed his dark brown mare, Prudence.

A crowd of children had arrived by this time. The Stanmores were walking their horses up and down. The sleet had stopped falling. Velveteen was excited by the other horses and every few moments he let fly at one of them, so that I had to go away by myself and ride round and round an empty piece of road. I knew some of the foot followers and Angela, a school friend, came across and said, “Haven’t you a mac? The forecast says snow.”

“I’ve left it at home. I’m not staying out long,” I answered.

I could see Sonia’s bay running backwards into the pack.

Tom cried, “Careful there, miss. Mind my hounds.”

Someone shooed the bay and Angela said, “She can’t manage him, can she? Do you think she’ll be all right?”

I didn’t want to worry about Sonia, who was no friend of mine.

“I expect so,” I replied, thinking, why have they put the horse in a twisted snaffle and running martingale? Everyone knew Miss Peel rode all her horses in plain or rubber snaffles and the bay was only young. I thought, they’re asking for trouble.

Captain Williams arrived on his liver chestnut and Tom blew a short toot on his horn, before we moved off towards a copse in the fields by the river.

There were twenty or more of us by this time. I brought up the rear on Velveteen, who was still inclined to kick. It was bleaker than ever by the river. Guy was talking to the Stanmore girls. Tom put hounds into the copse and three or four rabbits scuttled away in front of us.

“There are still some left then,” Captain Williams said. Presently Sonia began to have further trouble with the bay. He ran backwards, gave half rears and generally made a nuisance of himself. Then the first hound spoke, and he stood straight up on his hind legs and pawed the air. Sonia gave a little scream and at the same moment another hound spoke. Guy yelled, “Give him his head, Sonia or he’ll topple over,” and the bay wavered and came down with Sonia’s arms round his neck and her heels clutching his sides. It was all over in a minute, but I think it left most of us shaking.

“Gosh, that was a near thing,” said Chris who had just appeared on his grey mare. “If she’s not careful she’ll come a cropper before the day’s over.”

And now everyone was talking about the bay. “He’s no girl’s horse,” Captain Williams said.

“No wonder Miss Peel sold him,” exclaimed Guy. “I’m afraid you’ve been done this time, Sonia.”

“He was all right when we tried him,” drawled Audrey, who was still at one of the largest and smartest girls’ public schools though she was nearly eighteen. “He went like a peach. He can’t have been hunted before.”

I didn’t want to be drawn into an argument, but I’m fond of Miss Peel and I wasn’t going to let the cock crow thrice.

“It’s because you’ve put him into a twisted snaffle,” I said, trying not to sound angry. “He’s only young and it’s awfully severe for him, and he has been hunted before and he behaved beautifully.”

I thought, I sound a know-all and Guy will hate me and then there was a glorious burst of music and Tom was blowing the gone away; I forgot everything but the cry of hounds; the wind, the feel of Velveteen’s rollicking stride and the fields which lay in front of us.

There was a scramble at a gate and a slippery slithery bank which led us into a lane sheltered by tall hedges; there was flying mud and foot followers who stood back as we galloped past, and little boys on bicycles and a couple of dachshunds on a lead. Then we were through another gate and galloping across damp river fields; and Velveteen’s ears were forward, the other horses forgotten, his only interest the cry of hounds and the excitement of the chase. We came to a wire fence, which someone cut, and then to an osier bed with a ride down the centre and branches which slashed our faces. There was a smell of damp earth and stagnant streams before we were in the open again, galloping towards a cut and laid hedge. Hounds were close together and just behind them were Tom and his whip, Bruce. Above the sky was grey and behind us the wind whistled and howled across the open fields.

“This is fun,” cried Chris, who enjoys everything and is the most uninhibited person I’ve ever met. “One needs a run on a day like this. It’s perishing cold, but I love it, don’t you?” I said, “The cold or the run?” But the wind drowned my voice and Chris galloped on in silence, his bowler rammed over his ears, his cheeks glowing and a smile of pure happiness on his round, cheerful face.

Velveteen hesitated and then jumped so that I pitched forward as he landed and lost a stirrup. Further along Sonia’s bay took the hedge in his stride. And now hounds were swinging left towards a farmyard where cattle huddled by a fence and a tractor stood forlorn. Across the fields came the penetrating sickly sweet smell of silage, and Guy said, “That will stop them.”

“You mean the silage?” asked Chris.

And Sonia said, “I hope they don’t check. Benedictine’s just settling down. Honestly I was terrified when he reared.”

“I’m not surprised,” Guy answered, sounding sympathetic and smiling at her with kind brown eyes. “It was a beastly rear.”

Velveteen was blowing rather and I remember thinking, I’ll have to take him home soon, and hating the thought.

Then, to everyone’s surprise, hounds ran straight through the farmyard, across the main road and into the acres of plough beyond.

A man stood in the yard waving his cap. A dog pulled frantically at his chain and barked in an ecstasy of excitement. The road was wet and grey and very bleak. “He’s a big dog fox,” the man yelled.

“All right, mate,” we heard Tom reply.

There was traffic halted on the road as we galloped through the yard—people standing on their running boards, craning out of windows, waving and the smell of petrol, the stench of oil, and after that wet plough and the first of the rain on our faces, and in the distance a beech wood, and a little hill topped by tall pines.

Velveteen made heavy weather of the plough. One after another the field swept past us.

“Hard luck!” cried Chris.

I hoped hounds would check at the wood, but they didn’t, and now as I let Velveteen jog wearily across the plough I could hear Tom cheering them on, and a holloa from the far side, which made my blood run faster, and then the crash of music as hounds burst into the open again.

I should have turned for home then, but I didn’t. I thought, it will do Velveteen good to follow quietly for a little while; and when I came to the end of the plough, I pushed him into a canter and rain dripped on us from the trees, which were bare and stood like sentinels in the wood, and there were the marks of many hoofs and the ground was squelchy under us.

We came to the open again and I nearly cheered; for there barely a hundred yards away was the field standing alongside a patch of kale. My spirits rose. I waved to Chris and he called: “Lucky for you,” and I heard him laugh.

Guy turned in his saddle and looked at us. Then I saw that Sonia was having trouble with her bay again. His ears were back and he was ready to go backwards rather than forwards. I’m not an expert but I’ve ridden a great many different horses and I know all the danger signals, and one glance told me that Benedictine was going to rear the moment Sonia used her legs. Sonia’s face was very white under her bowler. Her hands were clenched tightly on the reins and she looked terrified. I’d better tell her to turn him round if he starts to go up I thought, and Chris’s eyes followed mine and he said, “She’s scared stiff, isn’t she?”

“So am I. I feel something awful’s going to happen,” I replied, and it was true. For whatever Benedictine was like when Miss Peel sold him, he was no horse for Sonia now; sooner or later there would be a battle and he would come out top, and what would happen to Sonia one didn’t know.

But the hounds were speaking again now. And everyone saw the big dog fox which came out of the kale and loped away across the bare fields towards a line of hills. I don’t know how many people hollered, but I know Guy’s was the finest of them all.

And then suddenly, as the field began to gallop, and Tom blew the gone away and hounds came out of the kale with a glorious burst of music, the bay reared again. I noticed Sonia’s white face and a lock of red hair which had escaped her net and lay across her forehead; and then, frightened beyond words I watched the bay paw the air with his forelegs. I saw him quiver and wanted to call, “Lean forward. Give him his head,” but no words came. I thought, he’ll come back to earth in a moment, God make him come down safely. But he didn’t. He stayed up there for another split second and I watched Sonia slip back in her saddle and pull his mouth, and although she meant nothing to me I was paralysed with fear. I saw his hind legs quiver and at last words came and I called, “Put your arms round his neck. Drop the reins.”

But it was too late. The horse’s hind legs shook, he rocked and then very slowly he toppled over backwards.

Only a hundred yards away Tom was still blowing the gone away. The cry of hounds still rang merrily across the fields. I dismounted quickly and found that my knees were knocking. Sonia lay in a crumpled heap. The bay clambered to his feet as I approached. He looked shaken and was dripping with sweat. I thought, why does this have to happen to me? I shall have to get an ambulance. Suppose she’s suffering from internal injuries? I’d better not move her—just put my coat over her. My hands were shaking too, and I thought, pull yourself together Jan, this isn’t the way to behave in the face of an accident. And then I saw someone coming back across the fields and it was Guy.

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Human: Jan Craigson, her parents, Chris Miller, Guy Maunder, the Stanmore girls (Sonia, Audrey and Susan), Angela

Equine: Benedictine, Velveteen, Fantasy, Daisybell, Prudence, Domino

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order

Bought for my daughter for her birthday next month. I had these original.ones when I was a child and hope she enjoys reading the new updated ones. Hopefully she will let me read them after her.

It’s a long time since I have read any of the Pullein -Thompson books, is nice to renew my acquaintance with them.

Loved this book. Excellent quality.