Jane Badger Books

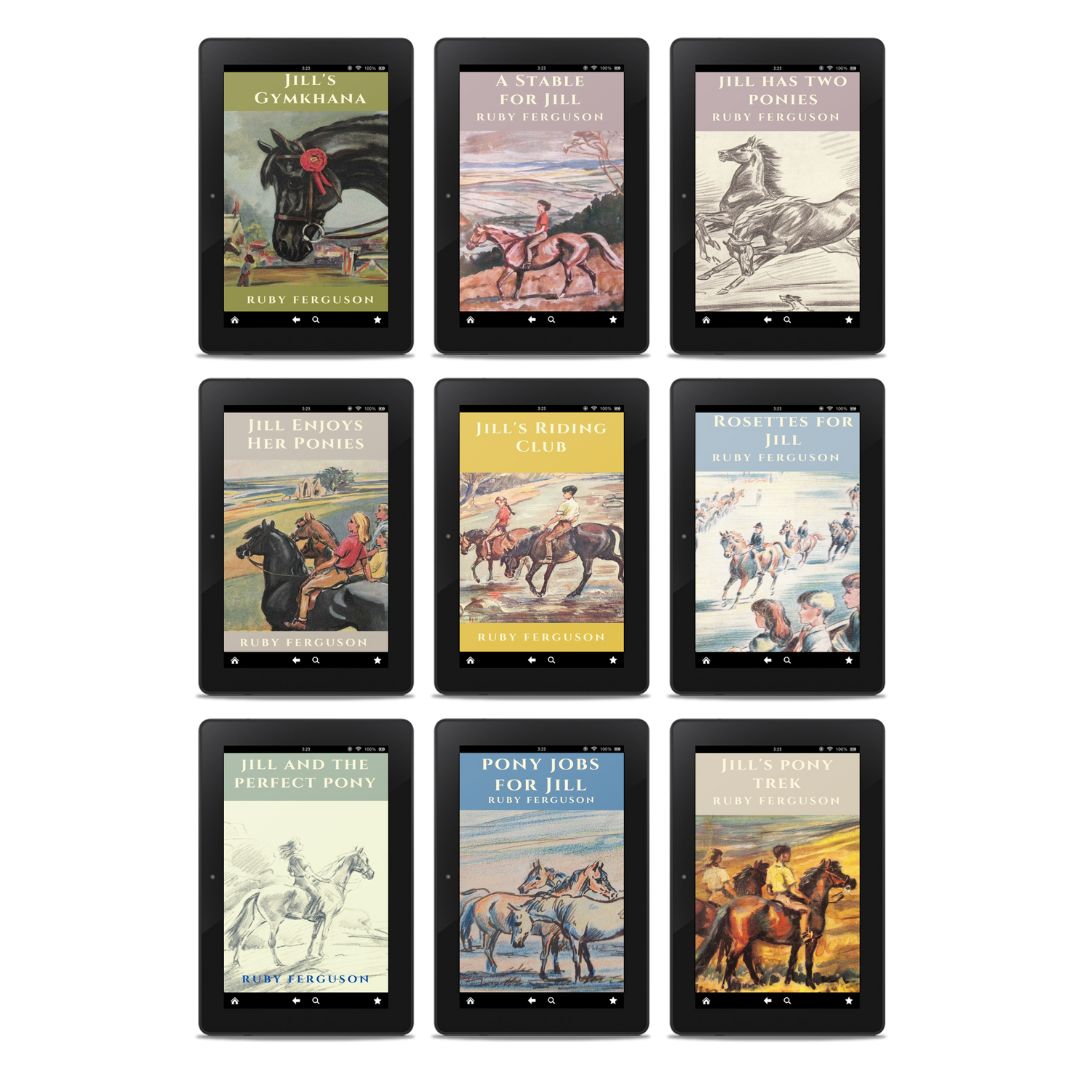

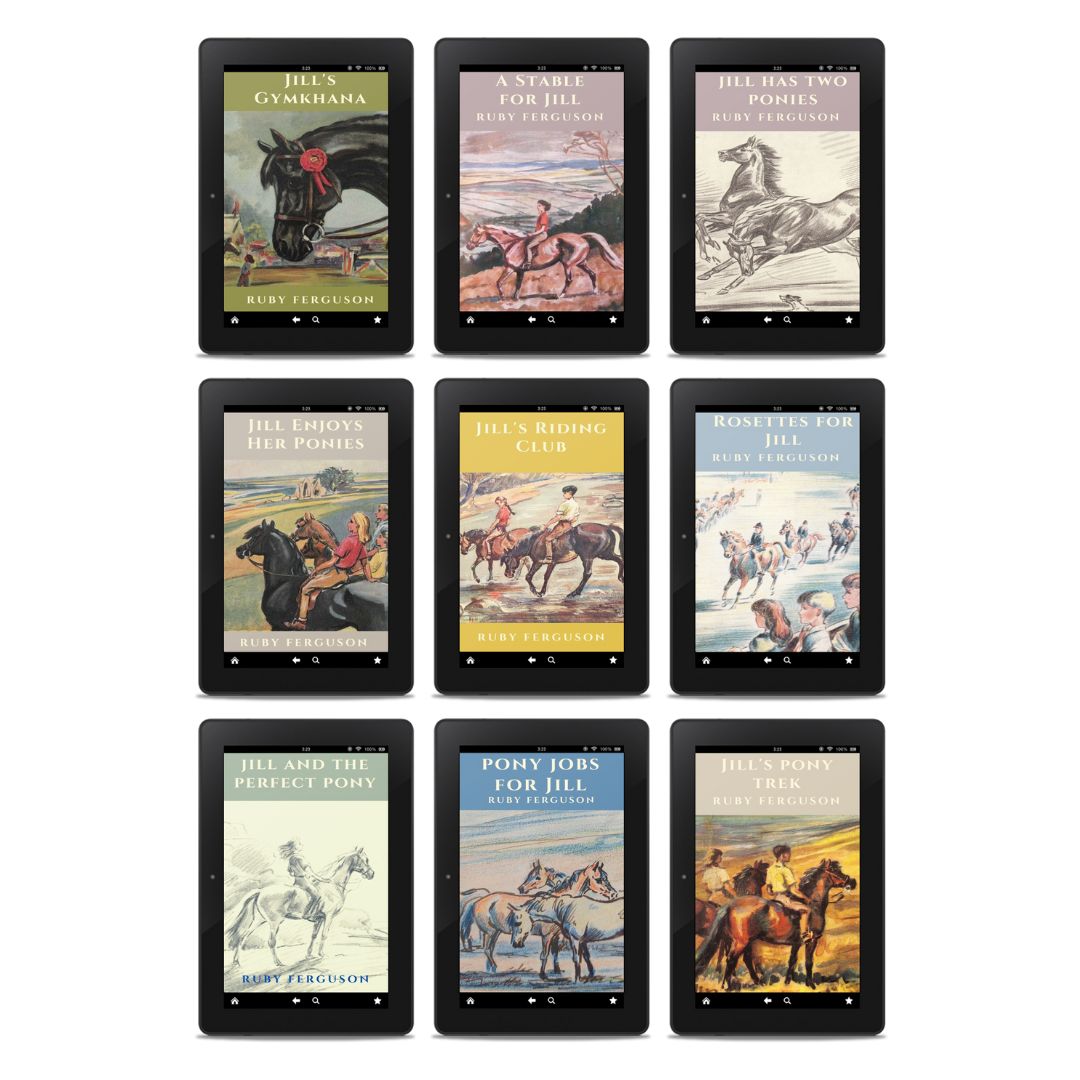

Ruby Ferguson: the Jill series eBook collection

Ruby Ferguson: the Jill series eBook collection

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Save and buy all nine Jill eBooks by Ruby Ferguson. You'll get nine separate eBooks:

- Jill's Gymkhana

- A Stable for Jill

- Jill Has Two Ponies

- Jill Enjoys Her Ponies

- Jill's Riding Club

- Rosettes for Jill

- Jill and the Perfect Pony

- Pony Jobs for Jill

- Jill's Pony Trek

Full price: £35.55 Collection price: £29.99

How do I get my books?

How do I get my books?

There's a link to download in your confirmation email. If you need help, the email from Bookfunnel, who handle our delivery, will walk you through downloading the files that work best for you.

How do I read my eBooks?

How do I read my eBooks?

You can read the ebooks on any ereader (Amazon, Kobo, Nook), your tablet, phone, computer, and/or in the free Bookfunnel app.

Will I get separate books or one volume?

Will I get separate books or one volume?

Separate books. It's just the same as if you bought the books separately.

These are new to me - I've read the first two now and greatly enjoyed them. Well-written, sympathetic character, fast-moving, and good for horse lovers. I would have loved them as a kid, too.

I was delighted to buy eBooks of the Jill series, having loved it as a child, so I can now read the books anywhere, though I still have both hardback and paperback copies at home.

One of the satisfying things about the books is Jill's skill at producing something out of raw material, whether it's the broken-down pony Pedro in A Stable for Jill, who with food and care proves to be a lovely pony, or the gymkhana Jill's Riding Club put on at the end of that book.

But one of the best things about the books is their humour, which, reading them as a child, I thought totally unique, but now realise was heavily influenced by the books of Edith Nesbit. The characters in The Phoenix and the Carpet, for example, are always telling each other to dry up, as Jill and her friends do to comic effect, while Jill's daydreams of saving the life of a wealthy person who would then reward her is a mirror of The Treasure Seekers' Oswald Bastable wanting to restore the family fortune, when he says "We could rescue an old [and by implication rich] gentleman from deadly Highwaymen". Additionally, while Jill & Co. are ordinary people with ordinary names, Ms Ferguson can't resist including characters with names like Mercy Dulbottle, Clarissa Dandleby and Captain Cholly- Sawcutt.

A second wonderful fact about the Jill books is the sheer verve with which they are written. Never for a moment are they staid or stodgy. Partly this is achieved by the use of comic or unusual verbs, e.g. "Ann's pony, George .. pushed his nose into the canvas bag, hoicked out another bunch of carrots, and .. bolted about six" (Jill's Pony Trek), or Jill "oozed down the silent stairs to the kitchen" (Rosettes for Jill).

Ruby Ferguson, again like E Nesbit, breaks the golden rule of writing that an author should never address her readers directly, and like E Nesbit, she gets away with it. E Nesbit: "Of course

I know that what you have really wanted to know about is .. what happened to Jane and Robert" (Phoenix). Ruby Ferguson: "I am telling you this disgraceful story to show you how hopeless I was, in case anyone who reads this book is hopeless too. Of course if any hard woman to hounds has read thus far she will now be scarlet with rage..and probably trying to get me prosecuted." (Jill's Gymkhana).

But Ruby Ferguson, as we can see in this last quote, always takes things a stage further with her own take on events, and very amusing it is too.

These were enjoyable books. I'm much older than the target demographic, but the characters are well drawn and the plots believable and moved nicely. The last few books went back in time, so Jill and her friends remained in school, but that's no drawback for this genre. I'm new to this author, but loved her work.

So brilliant to be able to revisit, in eBook format, books I adored reading as a child.

Really hope that the Pat Smythe Three Jays series can also be republished in this way.

So great to be able to get hold of these books in ebook format. Thank you!