Jane Badger Books

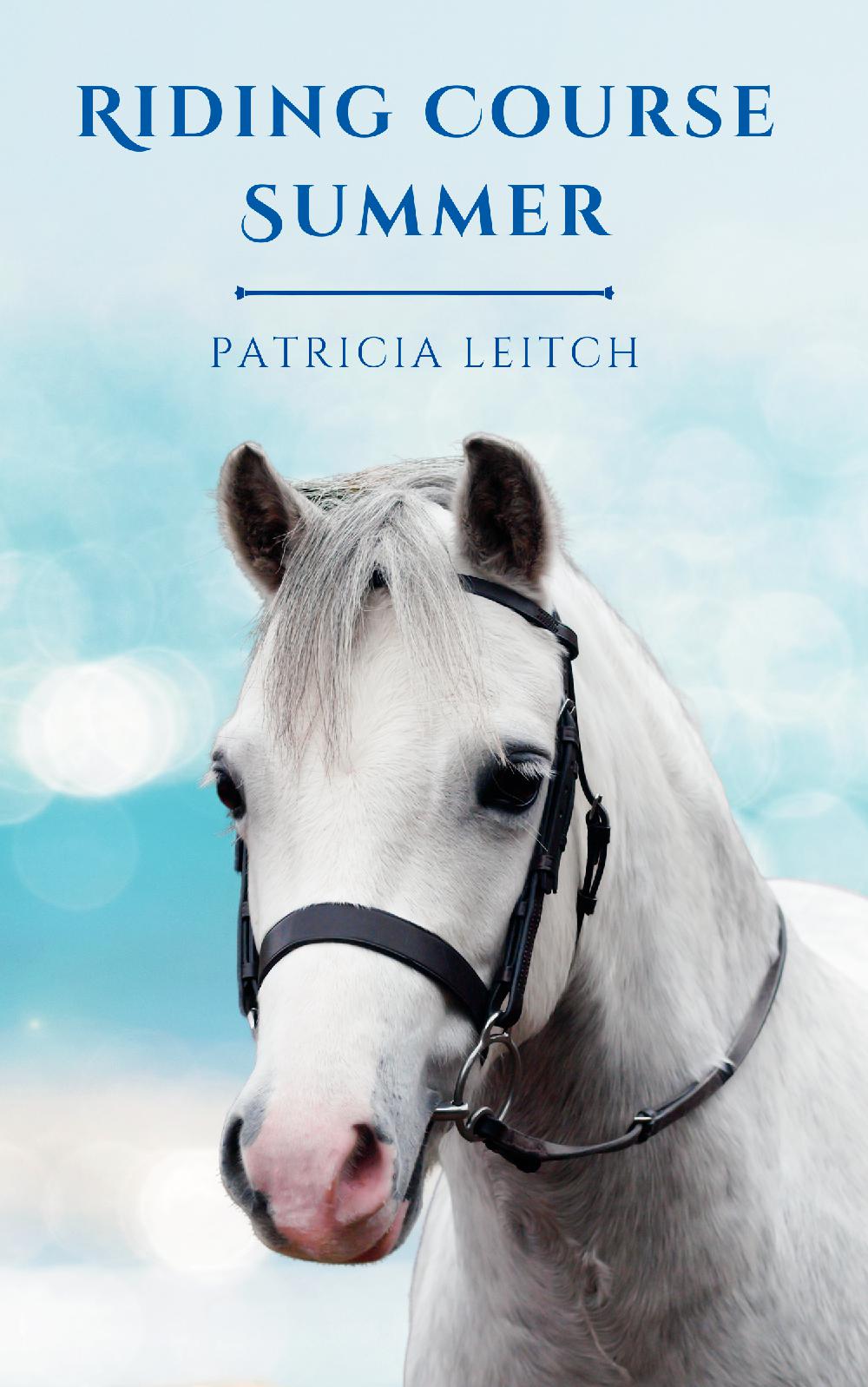

Patricia Leitch: Riding Course Summer (paperback)

Patricia Leitch: Riding Course Summer (paperback)

Illustrator: None

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

All Ann wants is to ride. She does ride her friend Angy's pony, Ladybird, and has the occasional ride at Mr Winton's stables, but none of it has made her a good rider. Looking round at the people she knows, none of them are any good either. Ann and Angy decide to do something about it. They'll start a riding club.

This is a reprint of the classic 1960s story. It's a brilliant feel-good read, and if you want transporting to a world where all you had to worry about was learning to ride better, this is the book for you.

Page length: 162

Original publication date: 1963

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

“D’YOU KNOW,” said my friend Angy, who has black curly hair and is eleven years old, “Not one of us can ride. We’re just about the most rotten riders you’d find anywhere.”

Dismally I agreed with her.

“Just look at this afternoon, we were all terrible. Perhaps there’s some excuse for you. You haven’t got your own pony but nearly all the rest of us have, and not one of us got round that potty little course without dozens of refusals and at least four jumps down. We’re absolutely awful riders!”

“Peter Gilmour got round clear,” I said.

“Peter Gilmour!” snorted Angy in disgust. “Galahad was out of control all the way, and every single time he jumped, Peter was left behind and caught him in the mouth. He’d a double bridle on him to-day, too. Why that horse goes on jumping I can’t imagine.”

We were coming home from an hour’s riding in the paddock of our local riding school. Angy was riding Ladybird, her fourteen-hand piebald pony, and I was walking despondently at her side. I knew that every word she was saying was true.

Our riding school is really more of a dealer’s yard than a proper school. Mr. Winton, who owns it, isn’t the least interested in teaching children. Most of the time he is too busy to be bothered with us at all. If you had your own pony you paid him half a crown an hour for the use of his paddock and jumps, or for riding over the moorland, which belonged to the stables. And if, like me, you didn’t own a pony, you paid six shillings and took your pick of the ponies and horses which happened to be passing through the stables that day. The first two or three times you went out, Mr. Winton usually managed to tack up your pony for you and see you mounted before he left you to attend to more important business; but after that, the saddling and bridling were left for you to do yourself. Because of this, people were always riding out of the yard with twisted girths, saddles that were right down on their pony’s withers, bits that were either too low or too high in their ponies’ mouths and drop nosebands that were nearly cutting off the pony’s breathing.

Customers were always being run away with or being bucked off. Children who had hardly ridden at all were sent out alone on ponies that shied violently at anything larger than a Bedford van, and nervous ladies were mounted on blood chestnuts that had only arrived from Ireland the day before. Really, considering the kind of things Mr. Winton did, it was surprising how few accidents there were. Most people fell off and the nervous ones got a fright and never came back, but a few pony-mad children like myself kept on going, because it was the only place for miles and miles around where you could hire a horse. Children who had their own ponies went quite often, because Mr. Winton’s paddock was large and flat, which is unusual where we live, as most of our fields are sloping and rocky. Mr. Winton had a good selection of jumps, and since he was always schooling green horses over them, any damage we did was never noticed.

“And look at to-day,” Angy went on, her dark eyes sparkling with rage at the thought. “When he does come down to the paddock with us what does he do? Just stands there and laughs. Honestly when I’m trying to make Ladybird jump and he stands there laughing I could … ” Words failed Angy. “Well I could anyway,” she finished.

“He put the course up for us,” I said.

“Because he wanted it up. He’d someone coming to jump that new bay mare he bought from the farmer at Dorlan.”

“Oh,” I said.

“And that roan thing you were on to-day! I don’t think it had ever seen a jump in its life before. Probably pulled a cart until a week ago. And for Mr. Winton to go chasing it over the jumps the way he did is utterly useless. It doesn’t teach the horse anything, and you were all over the ship when it did jump.”

“I know,” I said miserably.

Angy was coming to tea with us. She only lives about ten minutes away, but she spends a lot of her time at our house, which is large, built of grey stone, and surrounded by a weedy garden, against which Mummy struggles in vain. Angy’s own house is a small, modern bungalow with a pocket-handkerchief garden, which her father keeps under strict control.

We watered Ladybird at the bath under the outside tap and took her down to the garage cum loose-box. It used to be all garage, but since Daddy only has a scooter called Minnie, who fits comfortably into the shed, and since Angy was always being stranded at the kitchen door holding Ladybird’s reins, we cleared out the garage and decided that when Daddy’s scooter was in the shed and Ladybird was in the garage it could be a loose-box.

We took Ladybird’s tack off, and I took a dandy brush over her, while Angy fetched an armful of hay from the bale which she keeps in our shed. Then we left her stuffing herself and went into the house.

“Let’s hope your mother has something smashing for tea,” Angy said. “The way I feel just now, only iced melon with chicken to follow could cheer me up.”

“What about sausages?” I asked. “Because that’s what it is. I went for them this morning.”

“Ugh!” said Angy. “We had them for lunch.”

I opened the back door and we went into the kitchen. Mummy was standing by the cooker frying sausages and eggs.

“Well,” she asked. “How did it go to-day?”

“Terrible,” I said, warding off Floss’s attempts to wash my face. Floss is our mongrel. She is a beautiful pale primrose shade with black spots, a plumy tail and big spaniel eyes. People are always stopping us in the street and saying how nice she is, and how they’ve never seen a dog like her before, which isn’t surprising because Floss is unique.

“You know, we get worse and worse,” I said.

“Perhaps you had an off day,” said Mummy sympathetically. Long ago Mummy had abandoned any hopes she may have cherished about her daughter turning into a Pat Smythe.

“Three times,” said Angy. “And me once. Shall we set the table?”

“Yes,” said Mummy to the table bit, and “It must have been a beast of a horse you had to-day,” to the bit about me falling off three times.

“Not particularly,” I said. “It’s me that’s so rotten.”

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans:

Ann Harker, Liz and Mr and Mrs Harker, Angy, Mr Winton, Beth, Dianne Lynton, Peter and Allan Gilmour, Mark Stratter

Equines:

Quilt, Ladybird, Cracker, Galahad, Viper, Monty

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order