Jane Badger Books

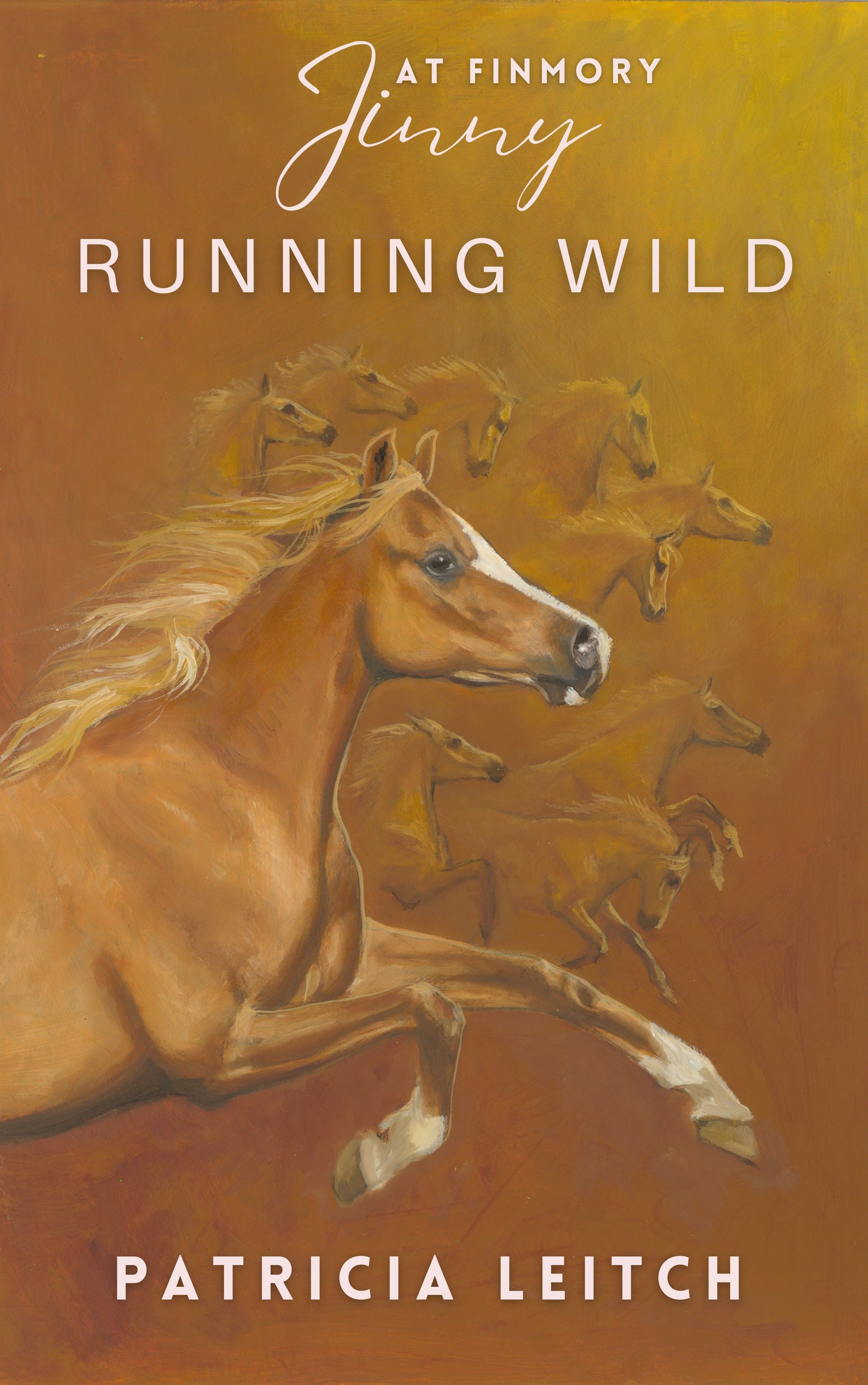

Patricia Leitch: Running Wild (eBook) Jinny 12

Patricia Leitch: Running Wild (eBook) Jinny 12

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Shantih, Jinny’s chestnut Arab mare, has to wait in a field until Jinny arrives back on the school bus and rides her back to Finmory. Fit and bored, she jumps out. What, thinks Jinny, can she do to keep her horse interested?

And what can she do to try and save the Wilton museum, where she painted the mural of the glorious golden horses? It is to be demolished.

Miss Tuke tells Jinny all about a long distance ride, ideally suited to Shantih, for Arabs are the best type of horse for endurance. But Clare Burnley, Jinny’s nemesis from a few summers ago, is back in the area, with a brand new horse bought just to take part in the endurance event. Clare is just as dismissive of Jinny as she was when they first met; just as rude about Shantih.

Jinny is determined to show Clare just how good Shantih is.

And in the end, she finds a way to save the golden horses.

Jinny series 12

Page length: 125

Original publication date: 1988

How do I get my book?

How do I get my book?

There's a link to download in your confirmation email. If you need help, the email from Bookfunnel, who handle our delivery, will walk you through downloading the file that works best for you.

How do I read my eBook?

How do I read my eBook?

You can read the ebooks on any ereader (Amazon, Kobo, Nook), your tablet, phone, computer, and/or in the free Bookfunnel app.

Read a sample

Read a sample

‘No!’ screamed Jinny Manders, waving her arms as she ran at full pelt towards Shantih’s field. ‘No! Stop it! No, Shantih! No!’

She raced desperately towards the field gate, swinging her school bag, half-blinded by her long red hair blowing across her face.

‘Get back! Get back!’ Jinny yelled, but she was too late. There was nothing she could do but watch as Shantih tore round the field, tossing and twisting her head, her mane storming over her hard neck and her tail held high, bannering over her muscled quarters, as her hooves daggered the soft ground and her scarlet nostrils trembled with whinnies of delight at seeing Jinny. She stopped, reared straight up, her forelegs raking the sky, then she touched down and charged full gallop at the gate.

Jinny clenched her teeth, dug her fingernails into the palms of her hands and watched mesmerized as Shantih rose over the gate in a high soaring arc, landed and came galloping straight towards her. Within inches of Jinny she splayed to a dead halt and pushed at Jinny’s arm, rubbing her head against Jinny’s shoulder.

‘But you shouldn’t, you mustn’t do it. Jumping out!’ Jinny raged, but although she tried to sound furious she had thrown her arms round Shantih’s neck, pressed her face into the pungent, sweet smell of Arab horse, and laid her cheek against Shantih’s silken mane.

For how could anyone tell off a horse who jumped a five-barred gate because she was so pleased to see you; who was so beautiful she made your heart ache; whose eyes were deep dark pools of magic and whose muzzle was softer than velvet?

‘Jinny Manders,’ Jinny warned herself. ‘Stop it! Stop it now. She only jumps out because she’s bored; because Mike got away from school earlier than you and has taken Bramble home.’

Jinny swung her school bag over her shoulder, grasped Shantih’s forelock and marched her back into the field.

Jinny was fourteen years old. Mike, her younger brother, was eleven. They lived in Finmory House in the northwest of Scotland. It was a four-square, stone house that stood in its own grounds looking down to jaws of black rock that framed the sea dazzle of Finmory Bay. Behind it was the rocky height of Finmory Beag, then reach upon reach of moorland and beyond the moors the far, humpbacked range of mountains.

Every school day Jinny and Mike rode into Glenbost—their nearest village—Jinny on Shantih, her chestnut Arab mare whom she had rescued from a cruel circus three years before, and Mike on Bramble, a black Highland gelding borrowed from Miss Tuke’s trekking centre but now more or less totally adopted by the Manders. Petra, their sixteen-year-old sister, went as a weekly boarder to Duniver Grammar while Mike and Jinny caught a ramshackle school bus to Inverburgh Comprehensive. Which was just as well, Jinny often thought. She couldn’t imagine Petra fighting her way into Glenbost through a winter gale. Petra liked talcum powder, women’s magazines and sitting in front of her mirror messing about with her face. She was going to be a music teacher when she left school and most of the time Jinny could not stand her.

‘That’s the third time you’ve jumped out,’ Jinny told Shantih as she brushed her down. ‘I’m telling you they’ll stop us using this field and then where will we be? Dad will make me sell you. He’ll say you’re dangerous and costing so much to keep. That’s what he’ll say.’

Shantih jumped away from the prickling of the dandy brush.

‘Get up with you,’ warned Jinny, meaning it, as Shantih’s hoof narrowly missed her foot. ‘Settle your idiot self.’

Jinny tacked Shantih up, organized school bag and hard hat, and led her out of the field. Prancing at Jinny’s side, Shantih sent clarion bursts of noise whinnying over the moorland, over the scattered crofts, the cluster of holiday cottages, the garage surrounded by its graveyard of rusting cars, the village school, Mrs Simpson’s sell-everything shop and the little church clutched tightly to the hillside beyond Mrs Simpson’s premises.

Jinny tugged the gate shut and, knowing that when Shantih was in a mood like this she would never stand still for her to mount, she sprang into the saddle, wriggling upright as Shantih cantered up the village street.

As they passed Mrs Simpson’s shop the door was thrown open. Mrs Simpson burst out and raged down upon Jinny.

‘Jinny Manders,’ she shouted. ‘Come you back here and be listening to me. I saw it all. That wild beast fleeing over the gate as though the devil himself were at its heels.’

‘Can’t stop,’ yelled Jinny, making no attempt to check Shantih.

‘It’s your father I’ll be stopping then and having a word with him. Or the police themselves. That beast is a danger to us all and we will not be having it.’

Mrs Simpson’s words were shouted after Jinny as she cantered round the bend of the road.

Once out of Mrs Simpson’s sight Jinny sat down hard in the saddle, brought Shantih to a trot and then to a jerky, unbalanced walk.

‘Enough of it,’ she said crossly, pushing Shantih into her bit, playing her fingers on the reins until she felt Shantih relax and start to pay attention.

It was, Jinny thought, most unfortunate that the second time Shantih had jumped out of her field she had almost landed on top of Mrs Simpson’s daughter-in-law who was pushing out her new baby. Even when Jinny had pointed out the fact that Shantih had completely missed the pram and no one had been hurt, Mrs Simpson had still clung doggedly to the fact that Shantih jumping out of her field was a danger to the whole community.

‘You’d think you were going round kicking people,’ Jinny told Shantih. ‘Or tearing them to pieces with your teeth.’

But Jinny really knew that it was serious. If Shantih started jumping out of the field when she felt like it anything could happen. She could be hit by a car or gallop on to the moors, fall and break a leg or sink into one of the moor’s treacherous bogs and literally never be seen again.

‘It’s your own fault,’ Mike had told Jinny. ‘Feeding her up as if she was a racehorse. All those oats. She’s ready to burst out of her skin. Wait till Dad gets the bill from Mr MacKenzie. He’ll splatter you.’

Jinny knew it was true but she could not bear the thought of Shantih losing condition over the winter.

‘True,’ she thought, knowing that if she cut down Shantih’s feed she would soon stop jumping out. ‘But not the whole truth.’

The whole truth was that Jinny wanted Shantih to be the way she was, so that a touch of her leg sent Shantih into a gallop; so that she cleared the stone walls on the moors as if they were nothing; was able to trot on effortlessly, taking joy in her own strength.

A tourist car speeding towards them sent Shantih into a sudden explosion of bucking, leaping from the road on to the sheep-cropped grass at its verge.

‘Shall we?’ demanded Shantih, clinking her bit, dancing her forefeet.

The moor stretched before them in a glory of freedom. It was Friday night. Homework could wait until the weekend.

‘Why not?’ agreed Jinny and felt her horse light up beneath her and with a plunging rear break into a gallop.

Sitting neat and tight in the saddle, Jinny gave Shantih her head. She felt the wind blow back her hair and whip tears from her eyes as she pressed her knuckles against Shantih’s hard neck and urged her on to greater speed.

When at last Jinny slowed Shantih down they had reached a rocky headland and Jinny could stare out over oceans of moorland. To Jinny’s left was a breath of smoke rising from the hidden chimneys of Finmory House, and in front of her the glittering brilliance of the sea.

Jinny jumped down from Shantih, not because Shantih was the least out of breath but because her book said that was the right thing to do when you had been galloping.

‘You’re as fit as a racehorse,’ Jinny told her. ‘That’s why you jump out. That’s why you’re so daft. You’re too bloomin’ fit. We need something to happen. A challenge. That’s what we need, not cutting down your oats.’

For this was how Jinny loved Shantih—hard and fit and full of galloping.

‘We need something to happen,’ Jinny repeated, holding out her hand so that Shantih could lip over her palm. ‘Something you can win to show them all.’

Jinny looked back towards Glenbost, thinking hard about not thinking about Mrs Simpson. She gazed over the familiar moorland, the quarry, Mr MacKenzie’s sheep folds, his small herd of Shetland mares and foals, and Craigvaar, the Burnleys’ posh, whitewashed house standing in its manicured garden and the glint of the burn rushing through the heather.

Jinny’s gaze jumped back to the Burnleys’ house. One of the loosebox doors in the stable yard was standing open.

‘Prowlers,’ thought Jinny, wondering if she should go down and shut it. The Burnleys lived in Sussex and only used their house in Scotland as a holiday home. Clare Burnley, who was about nineteen and seemed to spend her days doing secretarial courses or going to fancy cookery classes, usually came up with her parents, bringing her expensive horses up with her so she was sure to win everything at the local show. She was not Jinny’s favourite person.

As Jinny watched a light was switched on in the kitchen. ‘They must be here,’ Jinny thought. ‘Very early for the Burnleys. Wonder what horses she’s brought with her this time? Might be one I haven’t seen before … Wouldn’t harm just to look, just to ride past and look,’ and Jinny mounted Shantih and began to ride towards Craigvaar.

‘Only to see the horses,’ she assured Shantih. ‘Not to see that Clare Burnley.’

The moorland around Craigvaar was flat, sheep-nibbled grass with grey outcrops of rock. Jinny trotted Shantih to the white-painted fence that surrounded the garden, stable yard and paddock. Although the loosebox door was standing open there was no sign of life.

Halting Shantih Jinny stood up in her stirrups to get a better look. She caught a glimpse of a woman in the lighted kitchen but it wasn’t Clare or Mrs Burnley, perhaps Mrs Grant who cleaned for the Burnleys.

Then, just when Jinny was about to give up and go home, there was the sound of a heavy vehicle coming along the road from Glenbost. Jinny heard it slow down as it was driven off the road and along the rough track to Craigvaar. In minutes Clare Burnley’s flashy horsebox was rumbling down the drive, past the house and on to the stable yard.

Jinny got ready to hate Clare Burnley.

‘She’s at it again, carting her horses all the way from the south of England. Coming up here to laugh at us. To make up for last year when Shantih beat her.’

The box stopped but it wasn’t the solid, blonde-headed Clare who jumped out, but a smart wisp of a girl, wearing a tweed cap on her short dark hair, scarlet riding trousers and a waxed jacket. Jinny watched as the girl moved quickly round to the back of the box and with neat efficiency let down the ramp and led out a bay horse. He looked well over sixteen hands high, was bright bay with a thick black mane and tail and a vivid zig-zag of white down his face.

Jinny had not seen him before.

‘New horse,’ she whispered to Shantih, not thinking much of him. He seemed too thickset, too blocky; a horse sculpted out of heavy metal that should have been standing on a plinth in a city square.

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans: Jinny, Mike, Petra and Mr and Mrs Manders, Ken, Mr MacKenzie, Miss Tuke, Mrs Simpson, Nell Storr, Jo Wilton, Clare Burnley

Horses: Shantih, Bramble, Gatsby

Other titles published as

Other titles published as

Series order

Series order

1. For Love of a Horse

2. A Devil to Ride

3. The Summer Riders

4. Night of the Red Horse

5. Gallop to the Hills

6. Horse in a Million

7. The Magic Pony

8. Ride Like the Wind

9. Chestnut Gold

10. Jump for the Moon

11. Horse of Fire

12. Running Wild