Jane Badger Books

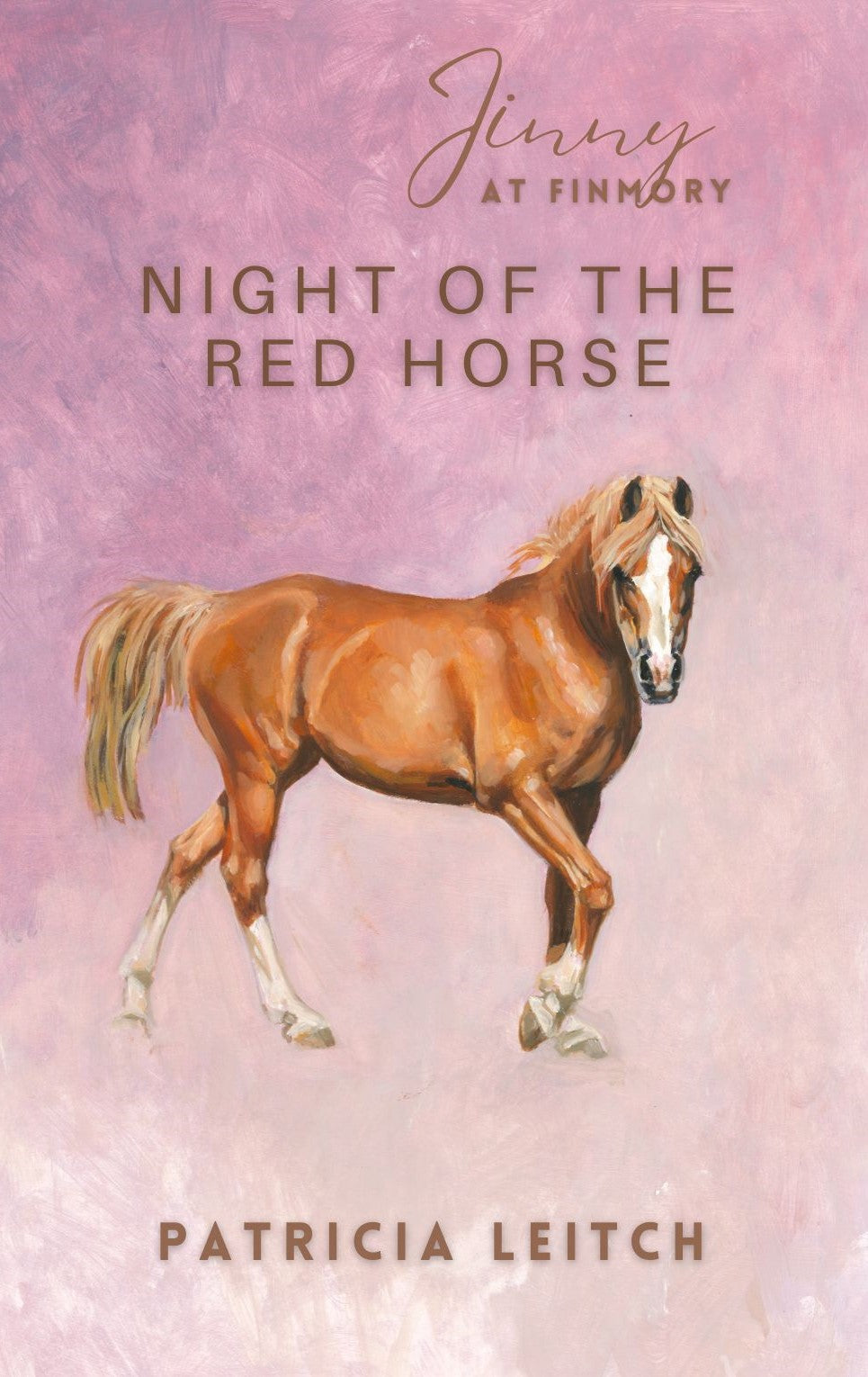

Patricia Leitch: Night of the Red Horse (paperback, Jinny 4)

Patricia Leitch: Night of the Red Horse (paperback, Jinny 4)

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Secretly, Jinny was afraid of the Horse. There was a strangeness about it, a power.

Something is happening to the red horse mural on Jinny’s bedroom wall. At night it haunts Jinny. Terrified, too terrified to sleep, she tries to escape the stalking horror of the red horse, filling her life with anything that will stop her thinking about it.

Sue and Pippen are back on the moors, and together they go to visit a dig. The archaeologists are searching for traces of a Celtic pony cult. Even the dig does not prove the distraction Jinny craves. The red horse is still there, and it wants something from Jinny.

Can she find the answer to stop the terror of the red horse?

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

This book is sent out directly by me, and you will get it within 2-5 business days, depending on what postal service you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

After the Manders had come to live at Finmory, Ken had arrived with Kelly, his grey, shaggy, yellow-eyed dog, and offered to help. Now he was part of the family. “Just as well he found us,” Jinny often thought. “Just as well for all of us.” For Ken’s rich parents wanted nothing to do with him. They sent him a monthly cheque through their bank. “So that they’ll know I’m not starving,” Ken said.

“Who’s here?” Jinny asked, going across the kitchen to look at Ken’s stones.

He handed one to her, holding it carefully between bony forefinger and thumb.

“A flint,” he said. “You can see where it was chipped to make a sharp edge on it. Made in the Stone Age and now you’re holding it.” He laid it reverently on Jinny’s open palm.

“I thought I heard you come in,” exclaimed Jinny’s mother, bursting into the kitchen. “Where have you been?” Jinny gave the flint back to Ken. She knew from the tone of her mother’s voice that things more urgent than Ken’s stones were about to overtake her.

“Jumping Shantih,” Jinny replied, while Ken turned himself off from their raised voices and went on staring silently down at his underwater, shimmering stones.

“All afternoon and all evening?” said Mrs. Manders in obvious disbelief.

“Well, more or less,” said Jinny, trying to remember anything else she might have done.

But her mother wasn’t really wanting to know.

“You’ve to go upstairs straight away and tidy your bedroom. It is an absolute disgrace.”

“Now?” asked Jinny in amazement. Remembering the strewn clothes, books, paints, paper and all the other things that were rioting over her bedroom floor, Jinny could quite see why her mother should think that it needed tidying up, but she couldn’t imagine why she wanted her to do it now.

“This very minute. Two archaeologists arrived hours ago wanting to see your mural. Luckily, before I took them upstairs, I had the sense to look at your room. It is a shambles, Jinny. I wasn’t going to clear it up after you so I told them they would have to wait until you came home. We’re all on to our fourth coffee, so do you think you could hurry up?”

“I don’t see why they should get into my bedroom … ” began Jinny.

“At once,” said her mother in the voice which Jinny didn’t argue with.

Jinny raced up the wide flight of stairs, ran along the landing corridor to where an almost vertical ladder of stairs led up to her room.

When she had first seen it, Jinny had known that this must be her room at Finmory. It was divided into two parts by an archway. The window on the left looked out to sea—down over Finmory’s wild garden to the ponies’ field and on to Finmory Bay. Waking in the morning, Jinny would lean out and call Shantih’s name, and her horse would look up and whinny in reply. The opposite window looked out over the moors and the high, rocky crags hustling up against the sky. It was in this half of the room that there was a painting on the wall which the archaeologists wanted to see: a mural of a red horse with yellow eyes that came charging through a growth of blue-green forest branches laden with white blooms.

Jinny could see what her mother had meant about her room. It was worse than usual. Jinny gathered up armfuls of clothes and pushed them into drawers, stacked books into piles, collected pencils, felt-tipped pens, pastels and paints into boxes and tried to sort out the sheets of paper that lay like autumn leaves after a gale, covering everything.

The walls, too, were covered with Jinny’s pictures—drawings, paintings, collages. They were mostly of Shantih and the animals that Jinny had seen on the moors—red deer, foxes, eagles, and the insects that lived their intense, secret lives in the same world as blind, gigantic humans.

Suddenly Jinny stopped clearing up. If the unknown archaeologists came up to her room they would see her pictures on the walls and Jinny hated anyone looking at her drawings. She wondered if she should make a fuss, go down and tell them that her bedroom was private.

“Jinny,” called her mother, still using ‘that’ voice, “are you ready? Can we come up?”

Jinny pushed a last pile of drawings under the bed, captured a stray sock and hid it beneath her bedclothes and glanced quickly around. Her room was not perfect but it would have to do.

“Yes, O.K.,” she called down, and waited, hearing footsteps and voices growing louder as they approached.

Jinny’s mother came in first, looking round quickly to see if Jinny’s tidying was satisfactory. She was followed by a large woman in a tweed suit, bullet-proof stockings and lacing shoes. Her white hair was cropped, her wrinkled skin a dusty yellow. A young man with pimples and thick glasses peered out from her shadow.

“This is Jinny,” said Mrs. Manders. “Jinny, this is Mrs. Horgan.”

“Freda,” said the woman, holding out a powerful hand to Jinny.

Jinny grasped it, said how do you do—but already Freda was striding towards the mural.

“And Ronald,” said Mrs. Manders, but the young man was trotting behind Freda, paying no attention to Jinny.

They both stood for a moment in front of the Red Horse, their heads thrust forward, staring at it, then Freda gave a snort of disgust.

“Useless,” she announced. “Totally useless. Obviously painted this century. Crude primitive.”

“Waste of an afternoon,” agreed Ronald. “No chance of an original underneath.” And he scratched at the paint with his fingernail.

“Well, I like it,” protested Jinny indignantly. “I like it very much indeed.”

Secretly, Jinny was afraid of the Horse. There was a strangeness about it, a power. When Shantih had been trapped in the circus, and Jinny had thought she would never see her again, she had drawn a picture of the Arab galloping free on the Finmory moors and pinned it on the wall opposite the Red Horse and Shantih had come to Finmory. Jinny didn’t really believe that the Red Horse could have had anything to do with bringing Shantih here, but then you never knew for certain about these things. You could never be quite sure about them.

“And it’s mine,” added Jinny, as if that settled the whole matter.

“Jinny,” warned her mother.

“Now please don’t get the wrong idea. I’m sure you’re very fond of the old fellow, but we’re looking for something else. Traces of a pony cult that we think might have existed in these parts. The Celts had many sacred animals—the horse, the stag, the dog, the boar and several others are all linked up with Celtic mythology. We’re excavating a Celtic settlement at Brachan, about twelve miles from here. One of the locals told us there was an old painting of a horse at Finmory House. We pricked up our ears when we heard that. There’s cup and ball markings on some of the rocks above Finmory. Wouldn’t mind excavating here sometime. Definite links with the Celts. So we took a chance and came over. Decent of you to let us see it, but no interest.”

“What’s a pony cult?” asked Jinny.

“The Celts worshipped the Earth Mother, and one of the forms she took was the goddess Epona, goddess of ponies and foals. Not so long ago, about the turn of the century, a statuette of Epona was found quite close to where we’re digging. A tinker found it, handed it in to a museum in Inverburgh. Still there. Utterly ludicrous, a museum that size sitting on a valuable piece like that. Ought to be in London.”

“I didn’t see it,” said Jinny. She had been to Inverburgh Museum with her teacher, Miss Broughton, and the other pupils at Glenbost school. “I was doing a project on horses and I’m sure Miss Broughton would have shown it to me.”

“Oh, not the Inverburgh Museum. That’s quite reasonable. The silly old joker who handed it in had to go poking down the back streets and give it to the Wilton Collection. Nothing but a dust dump and you cannot get them to part with a thing.”

“Wish I’d seen it,” said Jinny. She liked the idea of worshipping a pony goddess, or, better still, a horse goddess like Shantih.

“Are you interested?” asked Freda.

“She is if it’s horses,” said Mrs. Manders.

“Well, why don’t you ride over? Your mother has been telling us about your horse.”

“I’m not sure that I’ll have time,” said Jinny doubtfully.

“Can’t promise to produce another Epona while you’re there, but we’d show you round the dig.”

“Could Sue come?” asked Jinny. “To ride with me?”

“Why not? Bring sleeping-bags, bunk down for the night and give us a hand the next day. Two ponies might bring us luck.”

Jinny hesitated.

“It would be very interesting,” said her mother.

“Broadening my interests,” thought Jinny.

“Not tomorrow, but the next day?” suggested Freda, making it definite where Jinny had hoped it would remain vague. “Your father knows where the dig is. He’ll show you where to come.”

“Well … ” said Jinny doubtfully, thinking of course building and jumping Shantih, and how there was so little of the summer holidays left, and then school and probably masses of homework. “Well … ”

But Freda was already out of the room, Ronald pattering behind her.

“So sorry to have troubled you,” Freda said, standing in the doorway as she said goodbye. “One never knows, does one? Can’t afford to ignore any clue.”

She was sitting in their Land-Rover before she remembered about Jinny.

“See you on Saturday,” she called, starting up the engine. “And your friend.”

“It’s not absolutely definite,” Jinny explained to her father as they went back into the house. “She just mentioned that Sue and I could ride over and see the place where they’re excavating. It wasn’t absolutely settled. We’re going to build more jumps tomorrow and it really depends on how long that takes.”

“She invited you to stay the night,” said Mrs. Manders. “I think you should go.”

Page length: 224

Original publication date: 1978

View full details

Haven’t read them yet but loved them as a child and looking forward to diving in! Love the cover artwork! 🐎❤️