Jane Badger Books

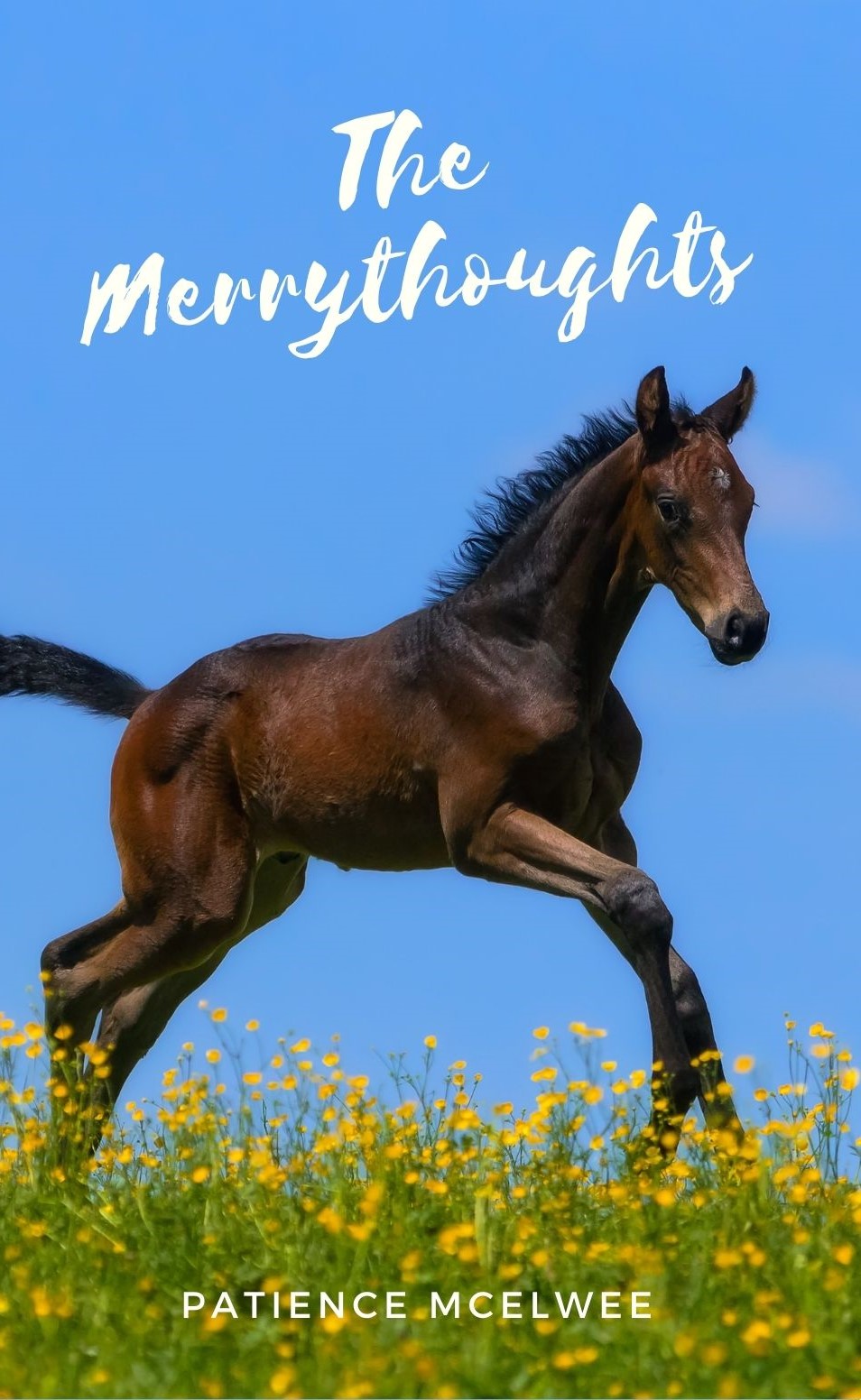

Patience McElwee: The Merrythoughts (paperback)

Patience McElwee: The Merrythoughts (paperback)

Illustrator:

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

They must all remember that they were in the public eye all the time, and that each member of the family had a part to play which might never be relaxed even at home.

Arabella and James are the Merry children: their parents make their living on television, telling other parents how to bring up their children, with their own beautifully behaved offspring as an example. Everything they do is a photo opportunity. But Arabella and James long to be normal; for people who like them for themselves. Most of all, they want animals of their own. When their father gets an unexpected legacy, it seems as if there might be a way out. Written in the 1960s, The Merrythoughts have their decendants now in all those families on YouTube and Instagram whose lives are laid bare to their fans.

Page length: 155

Original publication date: 1960

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

The Merry children were always being told how lucky they were, and how blissfully happy they ought to be. They were the most envied children at their school, and when they went to parties there was great competition to sit next to them and be their partners in games.

Everyone they met, of their own age, longed above all things to have parents who appeared on television. Mr. and Mrs. Merry were featured in a programme called Ask Us, and they gave advice over the air to other parents, who wrote up saying they were worried about their own children not being as happy or as good or as amusingly occupied as they felt they should be.

But the truth of the matter was that the Merry Parents, as they seemed so suitably called, were so busy earning a living telling other people how to make their children enjoy life that their own boy and girl, James and Arabella, were often dismally bored and in consequence unhappy.

They lived in a top floor flat in London, in a modem block of buildings that had no corners to explore, no possibility of secret rooms, no attics full of exciting, dusty, forgotten treasures. Everything worked smoothly at the touch of a switch or a button, and it was forbidden, in the terms of the lease, to keep any livestock more endearing than a goldfish or a caged bird. There was no garden down below, only a neatly paved courtyard without a single leaf or blade of grass to show the changing of the seasons.

All James and Arabella Merry knew about the country, and the birds and animals that lived off it, was what they could glean from books, and though they were given, at Christmas and on their birthdays, books galore, their parents’ wide circle of friends seemed to think they would be more interested in modern music and sculpture and pictures than in real live things. They appeared to think it would be an insult to give the children of such brilliant and intelligent parents the sort of things that ordinary children enjoyed.

Because nobody believed that they were in any way ordinary children. Miss Baxter saw to that. Miss Baxter was the Merry Parents’ secretary and ran their lives completely. She announced, the moment she took charge, that anyone who appeared on television could only hold down their position by suitable publicity. They must all remember that they were in the public eye all the time, and that each member of the family had a part to play which might never be relaxed, even at home.

It was she who saw to it that the children were out of the ordinary, dressing them in clothes that were shamingly different from other people’s, and insisting that their hair was cut quaintly, in short bobs with fringes, so that James was only distinguishable from Arabella because he wore trousers. At first, when they were very young, it had all seemed rather fun. Now they were both aware they were too old to wear identical, bright, chunky jerseys, over gaily coloured linen trousers in James’s case and heavily embroidered dirndl skirts in Arabella’s, and they were getting more and more ashamed to be known lovingly by thousands of viewers as the Merrythoughts.

They were sometimes taken into the country on Sundays, but Miss Baxter saw to it that it was always to somewhere where they could be reached by the clicking cameras of reporters, and they were warned they might not stray away from their parents’ side because viewers liked to think of them as the Perfect Family.

They did, on one memorable occasion, get as far away from London as the New Forest, after which a photograph appeared in a daily paper entitled ‘The Merrythoughts make a new friend,’ showing the children feeding a pony that strayed on to the road. The photograph was a great success, bringing in an even greater batch of letters than usual, and resulted in a programme all about children being encouraged to look after their own pets. The programme in its turn provoked a flood of letters about those same pets and the children who owned them, who, it seemed, practically omitted to feed and groom themselves, so wrapped up were they in all sizes and shapes of horseflesh, from Shetland ponies to hunters standing 15.1.

For James and Arabella themselves the expedition, so looked forward to, had turned into a torment. They could not get out of their memories the feel of the pony’s coat under their fingers, rough yet silky, the touch of the velvety, questing muzzle, the look in the big liquid eyes. They did not know that the pony belonged to a privately owned herd. They thought it was a stray, like the homeless cats they sometimes saw in London, which they longed to take in and establish with a saucer of milk in a basket by the artificial log fire in their square, pale coloured drawing-room, which was kept as tidy, by Miss Baxter, as if it might be thrown on the screen at any moment, featuring the Merrys at afternoon tea.

All the way home they discussed in whispers in the back of the car how the little brown mare might be conveyed back to London, how she could then be kept, perhaps in one of the old stables now converted into garages. They were given ample pocket money, because every time their father saw them looking bored he felt, poor man, that the only thing he could do was to plunge his hand deep into his pocket, and they thought they could afford enough hay and oats to feed so small a pony, with something left over for books to teach them something about riding and stable management. They were both very silent when they got home, from worrying about whether the pony was starving where she was, and how it was going to be possible to make the necessary arrangements for her rescue. Miss Baxter thought it was car-sickness, and said they must not go so far afield again.

The grown-up Merrys were out that night, at a party given by theatrical friends, so they did not know that Arabella had shed tears in bed, and that James, who was two years younger, only ten, did not know how to comfort her, beyond revealing the fact that he had seventeen and tenpence in his money box.

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans:

The Merrys: James and Arabella; Mr and Mrs Merry, Miss Baxter, Elaine Markham, Mrs Gasson, Hal Gasson, Mr Parker, Jennifer and Susan, Mr Handover

Equines:

Dandy, Poppet, Windfall

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order