Jane Badger Books

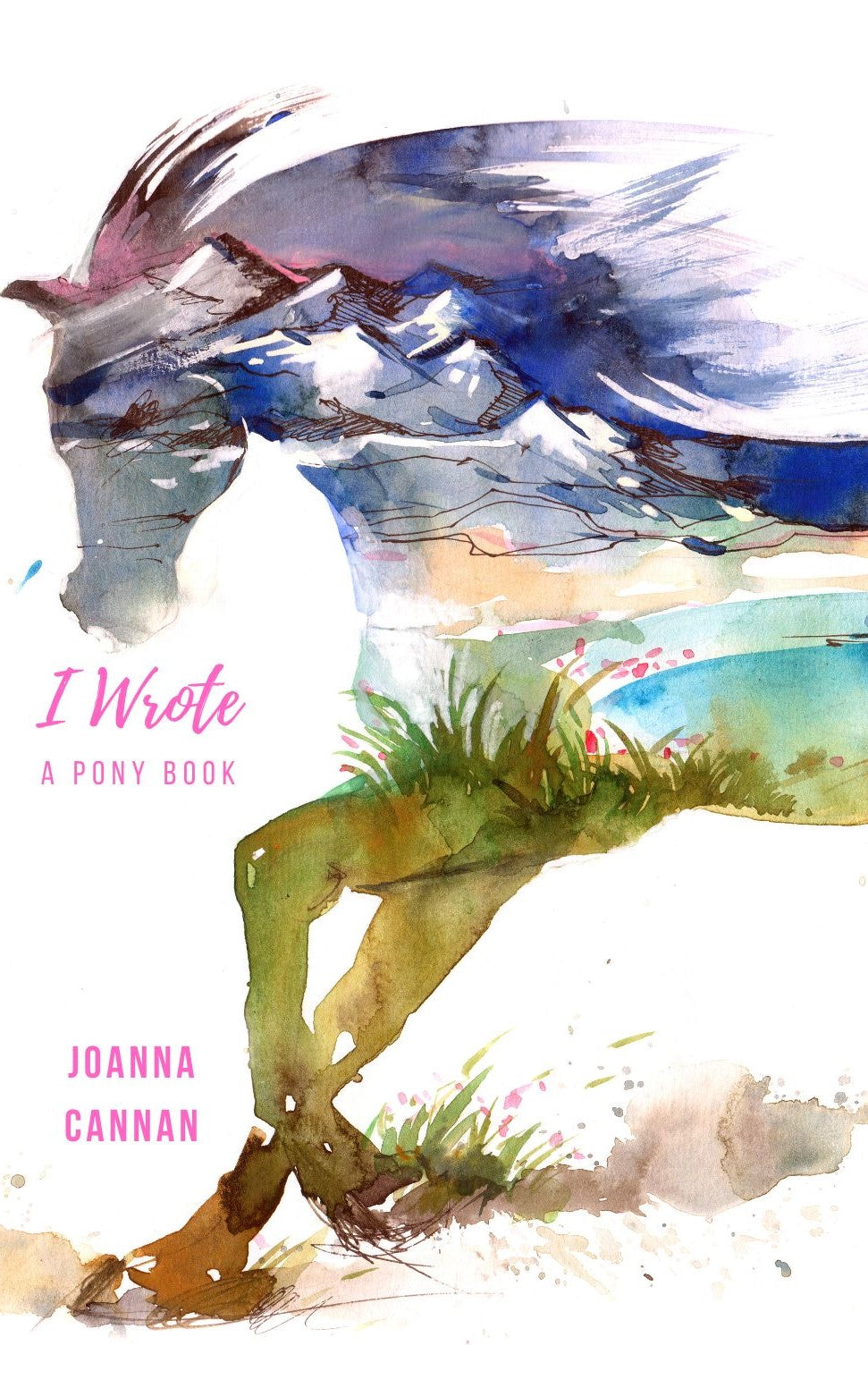

Joanna Cannan: I Wrote a Pony Book (paperback)

Joanna Cannan: I Wrote a Pony Book (paperback)

Illustrator:

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Alison is at boarding school. There is no love lost between Alison and her English teacher, and when Miss Boddington sarcastically suggests she writes a book, Alison decides that is just what she will do. Should she write something with her school-friends, or write an historical adventure herself? Or write about what she knows? Alison goes for ponies.

Writing a book is tough, particularly when you are at school, and the people you thought were friends turn out not to be. But Alison is a true Cannan heroine. She goes her own way, and she works to achieve what she wants.

The book's author, Joanna Cannan, takes some entertaining swipes at the pony-book genre, and if you've read any of her daughters' output (she was the mother of the Pullein-Thompson sisters) you can entertain yourself by spotting their titles in amongst those at which Joanna pokes fun. I Wrote a Pony Book is also a wry look at schoolgirl friendships and the strains of going home for the holidays, and is one of the few books to combine the school and pony book genres successfully.

Page length: 148

Original publication date: 1950

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

I am sure that if you met Miss Boddington, especially at the beginning of term, when, if you are like me, you are apt to contrast the stern and disapproving faces of your schoolmistresses with the dear furry faces of the dogs and ponies and cats and rabbits, and even ferrets, which you have so regretfully left behind you, you would agree with me that she is not the sort of person whom you would expect to inspire you with the high and noble aim of writing a book.

The ancient Greeks fancied that people were inspired to write books and paint pictures and make music by mythical beings called the Muses, but I have noticed that poems about the Muses generally complain that they have fled. Some people write in order to improve, but though this is a noble motive, their books are usually rather dull. Few people write merely for money, because you don’t get much. A fairly famous author has told me that the reason most authors write is because they feel that they would burst if they didn’t, but I must admit that that was not my reason. Believe it or not, I was inspired by Miss Boddington.

Miss Boddington teaches English at my school, Crispington, which is situated in what the prospectus calls that richly wooded and truly rural area known as the Dukeries, but is really the Midlands, that are sodden and unkind, as everybody, who likes poetry, knows from Hilaire Belloc’s poem. Miss Beddington comes from the Midlands herself, and when I was quite new she took an immediate dislike to me because one morning at breakfast she asked me why I was looking so glum, and I answered how could a person look otherwise, who had recently come to the sodden and unkind Midlands from the Border Country, with its hills and valleys, its watch towers and its rivers and its long and bloody history?

Munching a fishcake, made of the rather old fish we always have at Crispington, and potatoes, Miss Beddington said, “You absurd child, fancy quoting from that fat old Edwardian,” which made me furious, partly because I am fairly fat myself, but mostly because Belloc is one of my favourite poets. Later on I discovered that Miss Beddington hates all my favourite poets and writers and I hate hers, which is unfortunate, because English has always been my favourite subject, and when I went to a day school in Melrose, I was usually top of English, which made my otherwise awful reports comparatively pleasing to my parents’ eyes.

Miss Beddington, however, takes a very poor view of my essays, seizes every opportunity of taking off marks for untidiness—even slight blots—defaces my exercise books with sarcastic remarks in red ink, and calls all my best bits “unnecessary digressions.” Actually she likes you to put in exactly what she has told you in class and nothing that you yourself have thought of. I am sorry to say that I am rather a meek person. This is partly because I am very bad at everything, particularly all the things I should like to be good at. I would like to be good at games and athletics, at climbing trees and mountains, and I would dearly like to be the fastest woman to hounds on the Border. I would like to be tall and slim, with blue eyes and blue-black hair, and be called Diana.

As it is, I have got carroty hair and freckles, and I am small for my age, and as I said before, fattish, and my name is Alison. I am hopeless at games; I am always last in races; though I can swim, I hate diving, and when I do screw up enough courage to try, I do a bellyflopper. At gym, Miss Mallard, our games mistress, says I have no spring and will soon be round-shouldered, and taunts me with being what she calls a bookworm.

At home I am a disappointment to my parents, who, according to my old nurse, Jeannie, wanted a boy. My mother is a very good tennis player and my father, besides being plus two at golf, is a first-class shot. He took me out shooting once, but I cried whenever he shot anything, so he has never taken me again.

What I really love is riding, and I am extremely lucky in owning the nicest pony in the world. She is a dun-coloured Western Isles pony of fourteen hands, and her name is Marla. People who own show ponies used to criticise her because she is rather thick set, though not, of course, as thick set as a Highland pony, and also because in all the Children’s Jumping Classes, in which we had entered, we had never got farther than the wall. Of course this was my fault and not Marla’s, and it was also my fault that we were always last in Potato Races and first out in Musical Chairs. In fact the only thing I am any good at is lessons, and this is the irony of fate, when you don’t want to be.

For two terms I had suffered in meek silence from Miss Boddington’s sarcastic remarks, but one morning, at the beginning of the summer term, when she was giving back our essays, the worm turned. It was a cold but sunny morning in the merry month of May, and as Miss Boddington was merely telling other people the faults in their essays, I wasn’t attending. I was looking out of the window and contrasting the view of the hard tennis courts and the yellow brick wall of the gymnasium with the view from the windows of my home.

The windows of nearly all our bedrooms and sitting-rooms look out over the drive to a lawn that slopes down to the river Tweed, and the river, just before entering my father’s property, has been flowing in the deep shadow of high banks, covered with trees, and it is glad to be out in the sun again, so it ripples and splashes and sparkles and shines and, wherever we go about the house, we can hear it singing. Across the river is the ten-acre field where Marla lives; it is flat by the river, but farther way there are steep knolls with tall beech trees growing on them, and from upstairs rooms, like my bedroom and nursery, you look over the treetops to the three mysterious and historical Eildon Hills. Like many nice and beautiful things, the river is inconvenient. When I want to catch Marla, or even speak to her, I have to cross it. In summer I cross by stepping stones or paddling, but in winter, when the stepping stones are covered and it is too cold to paddle, I have to go down to the walled garden and cross by an iron bridge, erected, so it says, by my great-grandfather in the year 1885. It does not seem to have occurred to my great-grandfather that a person might want to bring a pony across the bridges and it has a multitude of openwork iron steps, both up and down, so, when I have caught Marla in the field, I have to ride her through the swirling waters of the swollen river to the farther shore. When the river is really in flood this is impossible, and Marla has to live in a small field behind the house, which she does not like at all.

I had shut my eyes so that I shouldn’t see the hard tennis courts and the gymnasium, and I was trying to conjure up a vision of Marla and the river and the beeches and the Eildon Hills, when Claire Hopcroft jogged me with her elbow, and I suddenly realised that Miss Boddington was speaking to me. I suppose she had been saying something sarcastic, because Enys Crowther, who is Miss Boddington’s favourite, was laughing scornfully. However, I only heard the end of the sentence, which was “… conceited enough to imagine that your childish opinions would interest me.”

I realised then that Miss Boddington was objecting to the bit in my essay on Victorian novelists, where I had contrasted an extract I like from Robert Louis Stevenson, whom she hates, with one I don’t like on the same subject from a modern historical novelist, who is a favourite of hers. “If you know so much about it, why don’t you write a book yourself, Alison?” she went on, and everyone except Henrietta Broughton and Claire Hopcroft laughed scornfully.

I boiled with rage. At the beginning of the class, while I was still attending, Miss Boddington had given back two essays, of which she approved: they were Harry’s and Hop’s and Hop had full marks and Harry nine out of ten. Had she but known it, they were both written by me in exchange for Harry and Hop doing my algebra, and they both repeated exactly what she had said in class about the Victorian novelists, only I had left one point out of Harry’s to look natural, because she is not so bright as Hop. My own essay was miles longer and, though I expect my own ideas were silly, I had at least taken the trouble to think them out and put them in. So, instead of saying nothing as usual, I doodled nonchalantly on my blotting paper and rashly said, “I dare say I will.”

It was Miss Boddington’s turn to laugh scornfully. “Do, by all means, Alison,” she said. “But I am afraid that we shan’t have the privilege of reading your words of wisdom. Not all the books that are written get published and I doubt that you will find a publisher who will share your obviously high opinion of your own abilities. Six out of ten. And as for you, Jennifer … ”

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans: Alison, her parents, Miss Boddington, Harry, Hop, Tamsin, The Help

Equines: Marla

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order