Jane Badger Books

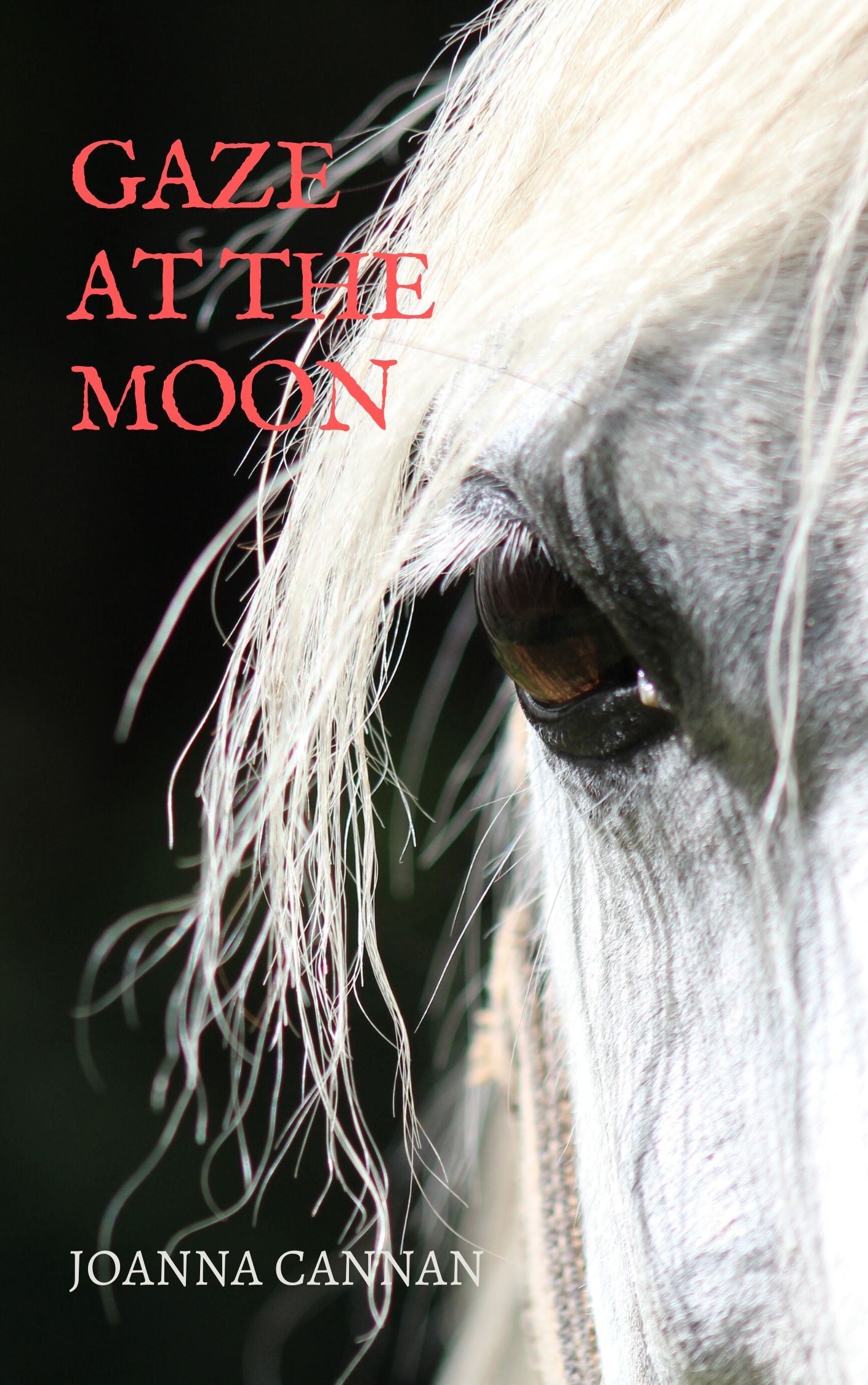

Joanna Cannan: Gaze at the Moon (eBook)

Joanna Cannan: Gaze at the Moon (eBook)

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Dinah and her family are moving from the country to the town, to a house that has mod-cons but nowhere to walk that smells of the woods and where you can see fields. What Dinah loves is the countryside, and horses, and painting. Her family don't always share her views, particularly her step-sister's deliciously awful boyfriend, Clive. But Dinah goes her own way. She carries on painting, and even finds somewhere she can ride. How Dinah forges her own path makes this a story that is just as involving as when it was first published in 1957.

Page length: 124

Original publication date: 1957

How do I get my book?

How do I get my book?

There's a link to download in your confirmation email. If you need help, the email from Bookfunnel, who handle our delivery, will walk you through downloading the file that works best for you.

How do I read my eBook?

How do I read my eBook?

You can read the ebooks on any ereader (Amazon, Kobo, Nook), your tablet, phone, computer, and/or in the free Bookfunnel app.

Read a sample

Read a sample

When the letter came to say that we had been allotted a council house, two of us were pleased and two were broken-hearted. The pleased ones were my step-mother and my step-sister, Judy. The broken-hearted ones were my father and me.

We were broken-hearted because we loved living at Speedwell Cottage. It was very old. The rooms were low and dark. The front door opened straight into the sitting-room, from which an open staircase led up to a tiny landing and the doors of the two bedrooms. After that there was a ladder, up which you could climb to the loft where we stored the apples—the Ribstons, the Bramleys, the Cox’s Orange Pippins and the Beauty of Bath. The loft had a tiny window set in the thatch. It was one of my chores to look after the apples; neither my stepmother nor Judy liked ladders or cobwebs, and in the course of years the loft had become my domain. In an old wooden box I had found there I kept what Judy called my “clutter”—my rather few books, my paint-box, odd sheets of paper which might do to draw on, pictures of horses cut out of newspapers, and the two moneyboxes which I didn’t want Judy to see because she always teased me about being a miser.

As I don’t want anyone to think that I am a miser, I will explain now that the money-boxes, one of which was made of wood by my Uncle Tom, who is a cabinet-maker, the other of a cardboard shoe-box by me, were marked respectively G.M. and A.S. G.M. stood for Grey Mare, and any money I made by doing things connected with animals or agriculture I put into that box.

A.S. meant art school, as my ambition in life is to be a painter and I wanted to go to an art school when the time came for me to leave Danesfield Secondary Modern, whereas my parents wanted me to be a secretary and Judy wanted me to be a hairdresser, as she is. When we left Speedwell Cottage, G.M. was much fuller than A.S. My father often gave me sixpence for weeding the garden or picking caterpillars off the cabbages; I had made ten shillings by looking after a lady’s hens while she was in Italy, and numerous other shillings by taking dogs for walks for people who were ill or lazy.

All that A.S. had was the money I had made by painting Christmas cards and selling them to my step-mother, who had only wanted three, and Judy, who wanted a great many but not subjects that I like to draw, not ponies or donkeys or any animal except cats, and then they couldn’t be cats like Kipling’s, that walked by themselves in wild wet woods waving their tails; they had to be kittens—fluffy ones doing something comical, like peeping out of boots or unravelling knitting. Really what Judy liked best was crinoline ladies, but I couldn’t bring myself to do more than three of them and six comical kittens. The only other person who bought my Christmas cards was William Woodley, a boy who lived near us in Pear Tree Cottage and worked on the farm. He bought three carthorse ones and later on I was annoyed to hear from my stepmother, who was friendly with his mother, that he had pinned them up in his bedroom instead of sending them away. I was annoyed because I thought this meant that he considered them too bad or too silly to send; much later on I discovered that it was because he liked them too much to part with them.

Unfortunately, when we moved house and I had to bring my things down from the loft, Judy saw my money-boxes and immediately jumped to the conclusion that G.M. stood for Getting Married. Everyone thought it was very funny that I should be saving up for that, especially as I am not at all pretty and have no boy-friends, but luckily in the excitement of moving this embarrassing joke was soon forgotten. One of the new things my step-mother had bought for our new house was a small bookcase for my bedroom, and I hid the money-boxes behind some large old-fashioned horsy books, which had belonged to my mother.

My mother had been a farmer’s daughter and when Judy complained that I behaved like a country bumpkin, Min—as I call my stepmother—used to defend me, saying that it was natural for me to like country things, which I think was very broad-minded of her considering how she hated the country. Step-mothers in books are always cruel or misunderstand their step-children, but Min was always nice to me and I loved her dearly. Judy was nice to me too, though we quarrelled sometimes, especially over Quest, our Border collie. Judy was quite kind to him and gave him far too much to eat, but both she and Min thought that he ought to live outside; they said he brought dirt into the house and laddered their nylons. When we moved into the town Judy suggested that we should have him put to sleep and buy a poodle. My father was furious.

My father was Judy’s step-father. Her own father, Min’s first husband, had been the manager of a grocer’s shop in the city. The shop stood in a very steep street and one day Judy’s father was standing at the door looking to see if the bacon van was coming. Higher up the street was a lorry delivering coal; it had inefficient brakes and suddenly it started to move. It went faster and faster and, with no one to steer it, in a matter of seconds it had mounted the pavement and was bearing down on a pram, which had been left outside the grocer’s shop by a woman who was waiting for the bacon. Without a thought for his own safety, Judy’s father sprang forward, snatched the baby from the pram—fortunately it was too young to be strapped in—and slung it into the shop as the lorry passed over him. As a result of his heroic act, the baby, though bruised, survived, but Judy’s father died the same night in hospital. The extraordinary thing is that this brave man was terrified of dogs and, like Judy, wouldn’t walk through fields with cows in them; and Min told me the story of his noble act because I laughed at Judy for screaming and running away when we were mushrooming in Farmer Waldron’s fields and his black carthorse, Captain, came lolloping up to us. Though I had not thought of it before, I agreed with Min that you should never laugh at people for being frightened of things that do not frighten you: probably you would be absolutely terrified of things that would not frighten them. I am not frightened of horses, cows or dogs, but I could never leap into the path of a runaway lorry to save anybody. But I am sure that Judy would.

Farmer Waldron was a very agreeable oldfashioned kind of farmer. Besides allowing us to mushroom in his fields, he said we could go wooding in Splashers Wood. Min and Judy did not like wooding; it spoilt their hands and laddered their nylons, they said; but I loved it, especially in Splashers Wood, where there are all sorts of fascinating creatures—foxes and owls and badgers. The trees are mostly oaks and there is a lot of undergrowth, but through the middle of the wood there is a track, used by the farm machines and Captain in his cart to reach the rough fields up on the hillside where Farmer Waldron grazes his sheep. It was on this track that I met with an adventure which, though not very exciting in itself, had far-reaching effects.

To take home the wood I collected, my father had made me a sort of cart by using some old pram wheels and a packing-case which I had painted blue. This was full of wood and, though I was nearly thirteen at the time, I was pretending to be Captain in his cart and plodding along the track with my hair pulled over my eyes like his forelock and my socks rolled over my shoes as fetlocks, when I heard a faint scream of “Mummy! Mummy!” and round a bend trotted a brown pony, which I recognised as a pony Farmer Waldron had recently bought for his daughter, Jill. In the saddle, clutching the pommel, sat, or rather, swayed, Jill Waldron, a pale thin child of six, who went to a private school in the town. I recognised the pony because it had been turned out with Captain and I recognised Jill because on my way to school I often saw her waiting for the bus at the corner of the lane, which leads to the farm.

When Jill saw me she screamed louder than ever. “Help! Help!” she cried.

“Okay. Hold on,” I shouted and quickly turned my wood-cart across the track. Then I began to run towards her, but on second thoughts I remembered that you should never rush towards animals, so I slowed down into what Min calls “Dinah’s Dawdle” and put on a calm voice in which I called, “Whoa, little fellow, whoa.” Greatly to my surprise, the pony slowed down into a walk, and when I reached it I had only to put my hand on the rein and it stood still.

Jill stopped crying. She said, “Naughty Topsy,” in a scolding voice and whacked the pony on the shoulder with a smart little riding whip she held in her hand. The pony jumped forward, but fortunately I was still holding her, so I said to Jill, “You silly idiot. Even a flick from a whip means ‘Go faster’ to a pony. I bet you hit her and she thought you wanted her to trot and that was why she took off with you.”

Jill said, “Mummy let go of her.”

At that moment Mrs. Waldron came stumbling along the track. She was fairly young and always very well dressed, and more interested in amateur theatricals than in farming. She was running with her head down, but when she looked up and saw us, she stopped and put her hand on her heart and panted. Then she walked up to us and said, “Oh, thank you, thank you. You’re Dinah Forrester, aren’t you? What a brave girl you must be. I’m so grateful.”

I said, “Gosh, I wasn’t brave. The pony was only trotting. When I said whoa she stopped. Honestly.”

“You’re very clever then,” said Mrs. Waldron. “I shrieked whoa, but she took absolutely no notice. Perhaps you’re used to horses. I’m not, but Mr. Waldron insists that Jill shall ride and until she can manage on her own I’m supposed to lead her.”

Jill said, “You let go of me. I shall tell Daddy.”

“I shall tell Daddy myself,” said Mrs. Waldron. “When Topsy jumped forward she knocked me off balance and I fell on my knees, so he’ll have to buy me a new pair of nylons. And I think we shall have to change Topsy for a quieter pony.”

While Mrs. Waldron talked, Topsy had been looking in my pockets. She had a very soft little nose and long eyelashes and a white star on her forehead. I thought it was a shame that she should be blamed for what I felt sure was Jill’s stupidity. I said, “Excuse me, Mrs. Waldron, but just now, when I was holding her, Topsy jumped forward. It was because Jill hit her with that whip, so I expect the same thing happened when you were leading her.”

One good thing about Jill is that she is truthful. She nodded. “I wanted her to go faster. I thought you’d run and keep up with her.”

“Run!” said Mrs. Waldron. “It’s all I can do to walk with you.”

Then I said, “Would you like me to take Jill out sometimes? I love walking and if Jill wants to trot I can run short distances.”

Mrs. Waldron said, “Oh, I should like it. It would be bliss, Dinah. I suppose I’d better ask Mr. Waldron first, because you’re not very old, are you?”

“I shall speak to Daddy too. I’d like her to lead me. I’m sure she can run faster than you,” said Jill heartlessly.

“I shan’t lead you if you bring that whip,” I said sternly.

“Silly old whip!” said Jill. “Here, catch, Mummy … .”

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Human: Dinah Forrester, Mr Forrester, Judy, Min, William, Clive, Jill Waldron, Catriona Gordon, Mary, Rupert Tranter

Equines: Air Frost, Topsy, Milkmaid, Jacko

Other titles published as

Other titles published as

Series order

Series order

Fabulous- love being able to access these and step back in time 😊