Jane Badger Books

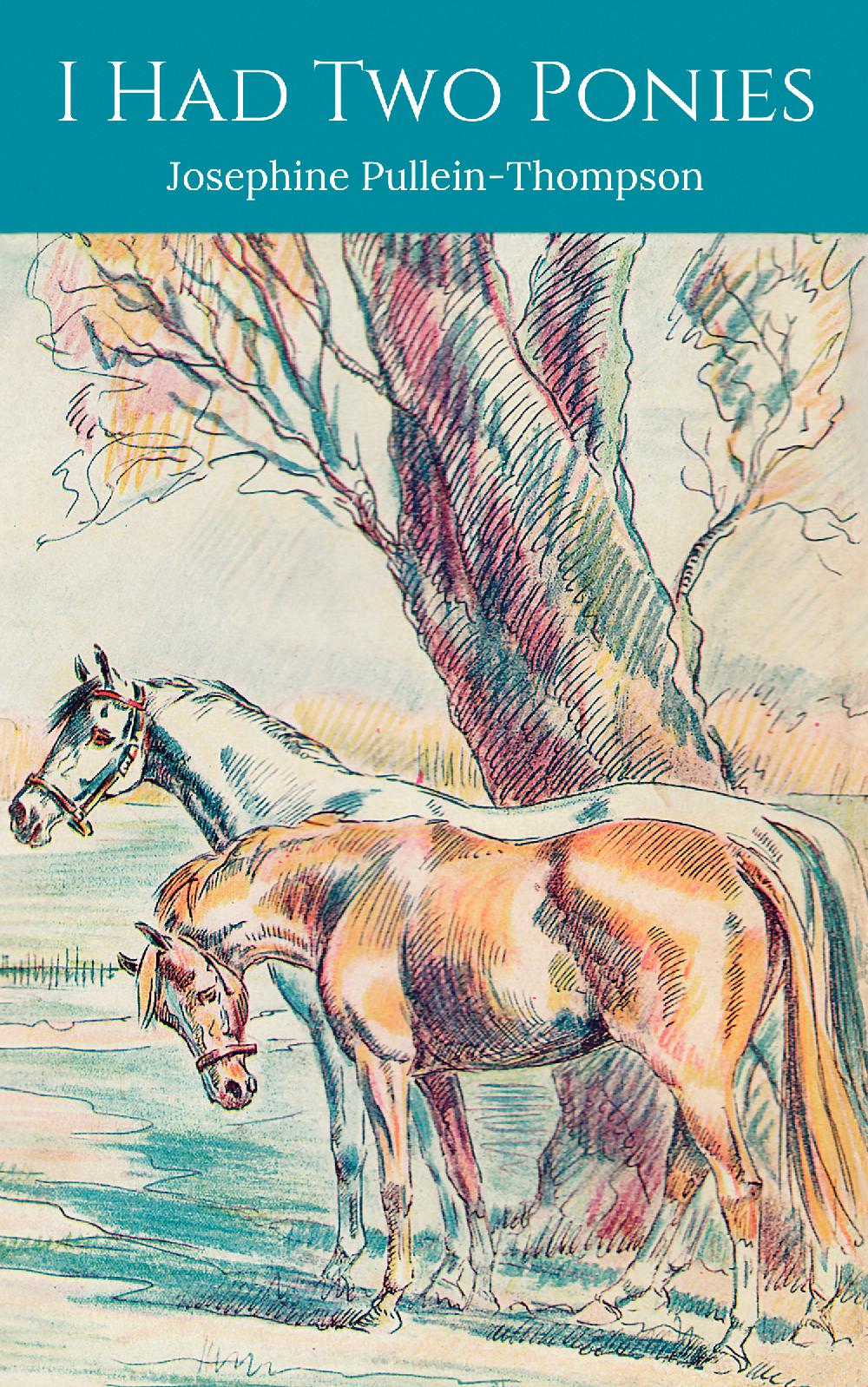

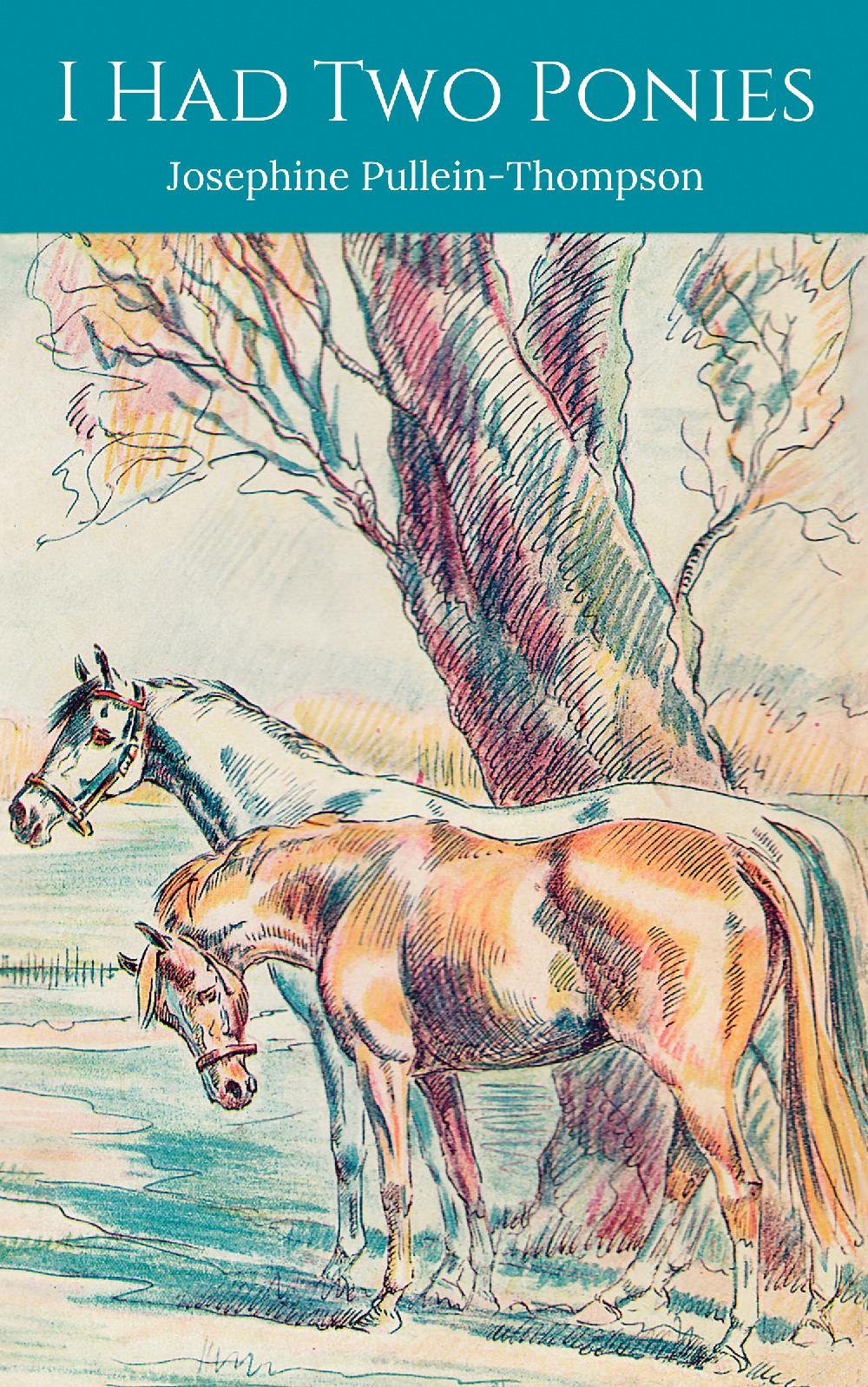

Josephine Pullein-Thompson I Had Two Ponies (paperback)

Josephine Pullein-Thompson I Had Two Ponies (paperback)

Illustrator: Anne Bullen

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

"I don't want to spend the Easter holidays grooming a beastly muddy pony."

When Christabel's father says "All right," to this, she doesn't expect that anything will happen. But it does. He sells her ponies. Christabel gets over it pretty quickly, but then she goes to stay with the Westlakes while her parents are away. It's never fun when you realise that people don't think very much of you, and the worst of it is, Christabel begins to agree with them. And she comes to bitterly regret selling her ponies. But will she ever be able to find them again? In a pre-internet age, it's not easy.

Fully illustrated edition with all the beautiful original illustrations by Anne Bullen

Page length: 226

Original publication date: 1947

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

I hope that you won’t take so violent a dislike to me in the first pages of this book that you slam it shut and, saying “Ugh! one can’t possibly read about such a beastly girl,” throw it aside.

I know now how awful I was and I still blush when I think of some of the things I said and did when I first went to stay with the Westlakes. But during those Easter holidays events happened which changed me a great deal and, if you want to know what they were, you must stifle your disgust and read on.

It was at the beginning of the Christmas holidays that my parents told me they were going abroad. Apparently, Daddy’s business in India wasn’t being run properly and, as he is the sort of person who believes that if you want a thing done properly you must do it yourself, he had decided to go out and put the matter right. Mummy, who was bored and thought a change of scene would be nice, was going with him.

Naturally, I wasn’t very pleased; few people are when they find that they have got to spend half-term at school and the Easter holidays with complete strangers, and I am afraid that I grumbled a good deal. Daddy said that he was sure that I would like the Westlakes; he had been at school with Mr., who was now a well-known actor, and Mummy thought that the companionship of the two girls, Gay and Lucy, would be nice for me. Nanny was the only person who sympathised with me; she said that now Daddy was a Lord he oughtn’t to demean himself by bothering about business and that if she was in his place she would wash her hands of it. But then she could hardly be expected to approve, because Mummy had decided that this was an opportune moment to give her notice.

Except for the actual Christmas celebrations, the whole holidays were completely ruined by my parents’ tiresome arrangements. Daddy seemed to think that this was a suitable time to do all the things that we had been putting off for years: he sacked Charles, the footman, who always became nervous at dinner parties and dropped or clattered the crockery, and the head gardener, because he had never been able to grow carnations; and then he started to bother about the ponies. They had been a birthday present from my parents and I was proud of them for they were both good-looking and had been very expensive.

But I had only ridden Amber, a golden chestnut, about six times in the ten months I had had him, and Daydream, a grey mare, even less times than that. I must confess, and, in my imagination I hear your gasps of horror, that I never really liked riding. Perhaps rides accompanied by Small, our groom, on Daydream, or on Daddy’s hunter, King Cole, were not very amusing, but I think really that I was just rotten to the core. All my friends thought that I was very lucky to have two such smart ponies, especially those who had no pony of their own, or who had to share one with several brothers and sisters. I would have been quite glad to lend my ponies to some of these people but Small didn’t approve; he said that they were all worse riders than me and would spoil the ponies, or would let them down on the roads and break their knees. Actually this was nonsense, as I discovered afterwards, and I think Small must have been afraid that he would have to clean the tack.

Daddy had often grumbled before that the ponies stood in the stable, month after month, eating their heads off; and dozens of times he had threatened to sell them, unless I rode more often. But I used to cry and say that I loved them and that he had given them to me and couldn’t take them away, and nothing had ever happened. So, of course, when he started again in the library after dinner, I didn’t take him very seriously.

“What do you want to do with those ponies of yours, Christabel?” he asked. “I’m not going to have them standing idle in the stable while you’re away. I’m sacking Small and lending King Cole to Colonel Stanmore for the rest of the season. All the Westlake kids ride, I believe, so, if you don’t want to feel out of things I should certainly take one of the ponies with you, but you’ll have to look after it yourself and keep it turned out.”

“I don’t want to do that,” I replied. “I hate riding grass-fed ponies; they’re always dirty.”

Daddy looked rather cross. “A very foolish reason,” he said, “but obviously, if you’re not keen, we’d much better sell the animals. I’ll tell Small to send them to the horse sale next Saturday.”

“Oh, no,” I said, “can’t they be turned out in the park and then we can get a new groom when you come back?”

“No,” said Daddy firmly, “I’m fed up with seeing those ponies doing nothing, I wish I’d never bought them. Either you choose one to take to Underwood Farm and I sell the other, or I sell them both.”

“I won’t take either of them,” I said, stamping my foot. “I don’t want to spend the Easter holidays grooming a beastly muddy pony.”

“All right,” said Daddy, “we won’t say any more about it.”

I didn’t expect anything to happen; I thought that Daddy’s words were empty threats and that my ponies would continue to stand in the stable or wander about the park; and on Sunday, as usual, when it was fine, I walked down to the stables with their lumps of sugar. To my surprise, the familiar heads were not looking over their doors, nor were the ponies in the park. I realised with a start that Daddy must have carried out his threat and sold my ponies.

At first I felt cross and sniffed into my smart linen handkerchief, but after a few minutes I realised what a lot of unpleasantness it would save: Daddy wouldn’t grumble because I didn’t ride the ponies, my friends wouldn’t be able to ask for rides and Small wouldn’t be able to complain if I gave my friends rides. So I stopped sniffing and walked into the house and started to fiddle with the expensive radiogram which, among other things, my parents had given me for Christmas.

The Christmas holidays passed quickly. Neither Daddy nor I ever mentioned the ponies again, but the parents really were very tiresome, talking endlessly about what clothes they would or would not take and if Monk, Mummy’s lady’s maid and Dale, Daddy’s valet, would be enough English servants, or whether they ought to take cook. Daddy said that an Indian cook would be quite adequate but Mummy said that she was going to give dozens of dinner parties and that she was sure that the Indian wouldn’t know enough dishes. Then Daddy had horrid business friends to stay so that he could discuss business with them at the same time as he saw that the packing was done properly. Altogether I was glad when the holidays were over and I was driven back to school with even more trunks than usual, stuffed with all the clothes which I might need during the Easter holidays as well as my school clothes.

At school, my friends were all very sympathetic about my misfortune in having to spend the holidays with horrid horsy friends of Daddy’s. Ann Dermott, my best friend, and I often imagined what the Westlakes would be like; at night — to our great delight we were sleeping together this term — we sometimes imitated them. Ann liked to be Gay and she was always very uncouth. Mummy had told me that the Westlake girls didn’t go to a decent school like Bramblewick Hall but were taught by someone in the village, so Ann and I thought they must be very peculiar. Ann said that they would be dirty, but I said I was sure that Daddy’s friends wouldn’t be as bad as that and I refused to agree when she said that actors were lazy, selfish, conceited and bad-mannered — her father was a business man, like mine. I argued, and, quoting Daddy, told her that successful actors weren’t like that; it was only the bad ones, who went on the stage because they thought it was an easy or glamorous life, who had these faults. However Ann wouldn’t agree with me and we argued quite angrily until matron came in and rowed us for talking. After that we didn’t dare speak a word in bed for several nights because we knew that if we were caught again we would be separated for the rest of the term.

As the holidays drew near I was filled with self pity and I bored everyone by grumbling about the horrid time I was going to have; then someone, I think it was a very earnest girl called Gillian, suggested that I should convert the Westlakes from their horrid ways, improve their manners and earn their undying gratitude. This idea pleased me and I soon began to look forward to re-educating the poor ignorant Westlakes and I didn’t feel nearly so miserable as I had expected when, after a week of exams, the term was over.

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans: Christabel, the Westlakes: Gay, Lucy, Simon, Adrian,

Equines: Amber, Daydream, Dauntless, Wisdom, Shadow, Adolphus

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order