Jane Badger Books

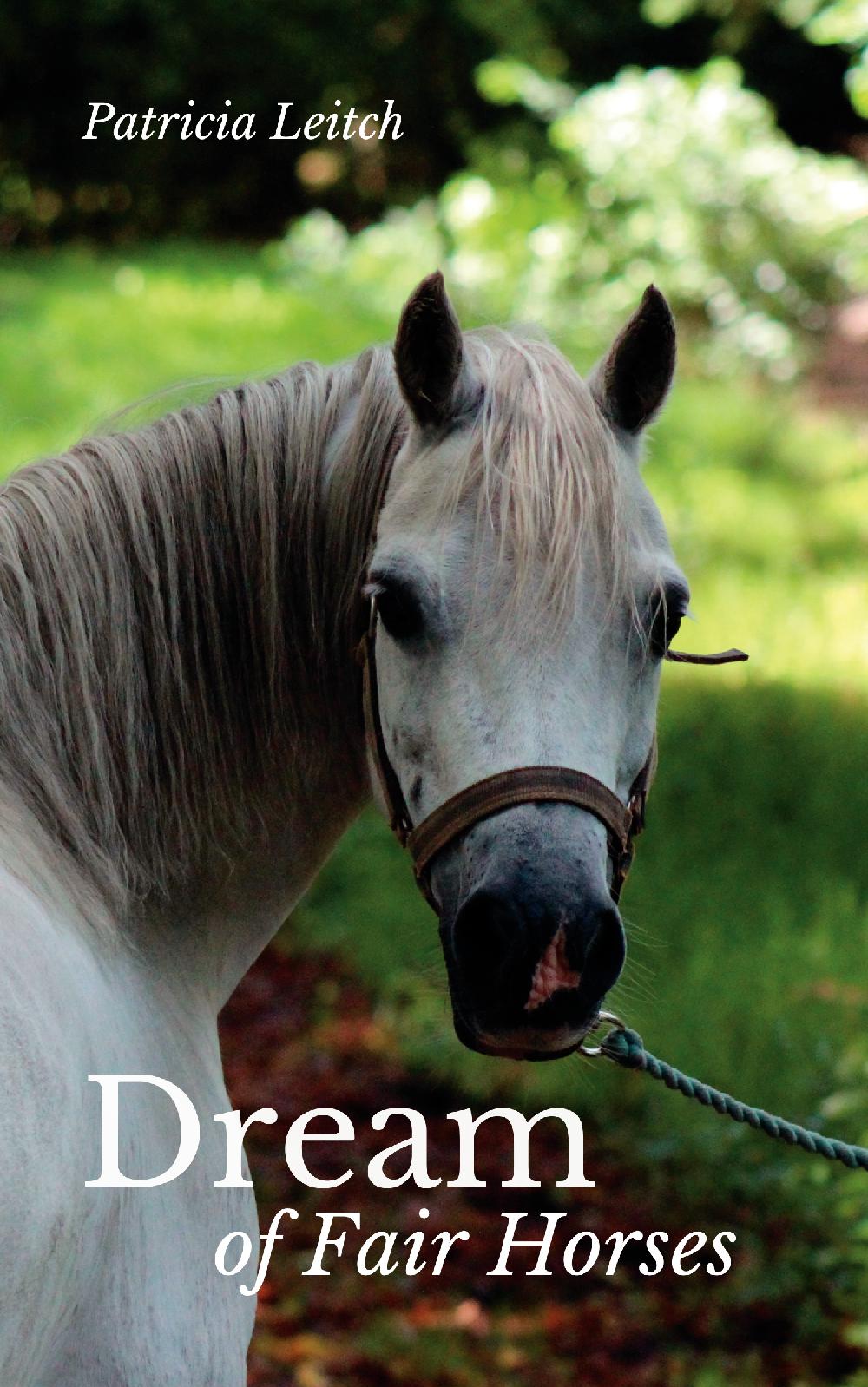

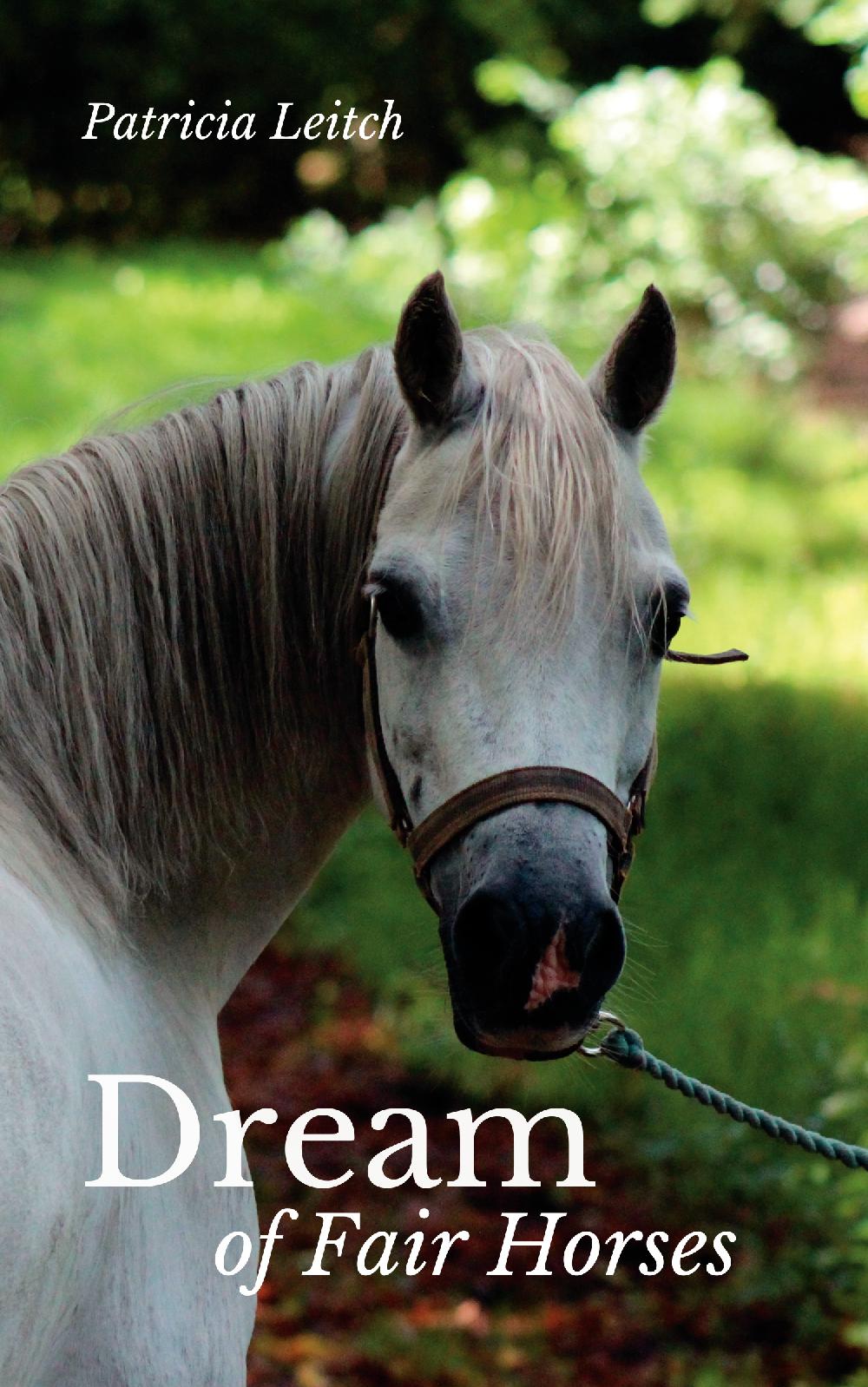

Patricia Leitch: Dream of Fair Horses (paperback)

Patricia Leitch: Dream of Fair Horses (paperback)

Illustrator: None

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

'In all my life, I had never seen anything as beautiful as this grey pony ... '

Gill Caridia and her family are on the move. Gill's father writes the sort of book that literary papers love, but which few people actually buy. And then he writes a detective story that sells so well he buys back the house in the countryside where he grew up. It means change for all the children, but for Gill it means the chance to find horses, and not just horses but to ride at Wembley. But Gill learns that no dream comes without cost. This passionate and vivid story, which takes Gill from the age of 11 to 13, looks at what it really means to own something.

Page length: 202

Original publication date: 1975

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

When Marcus was born Daddy looked down at his third son and seventh child and said that from now on things were going to be different. We were going to put down roots, that we had tinkled on tin feet for too long.

And he kept his word. When Marc was one we moved to Hallows Noon and we lived there for nearly two years which is a record for our family. Until Hallows Noon we had never stayed anywhere for more than a year.

It was at Hallows Noon that I found Perdita. Her name means The Lost One but I didn't know this until the end, when I was about to lose her.

Marcus was born at 37 Dunsmoor Road, a red brick house sandwiched in a row of identical red brick houses. We had been there for only a month, but already Libby had joined the Brownies, Fran had sung at an old age pensioners' concert and Dante, our Afghan Hound, had chased the postman, the dustbin men and dozens of other people out of the garden.

With the addition of Marcus there were seven of us. Ninian, my eldest brother, was sixteen and struggling to be himself; Torquil was fifteen and lost in a world of bugs that crawled and buzzed and squirmed; Francesca was fourteen, passionately addicted to singing in public yet cursed with total tone deafness; I was twelve and terrified in case I should die before I had ridden in the Horse of the Year Show at Wembley; Libby was nine and a Brownie; Una was six and still cried when the children at school teased her about Daddy; and Marcus merely existed.

Our father is Laurence Caridia. He is a great author who writes strange novels which are reviewed in The Sunday Times and intellectual magazines. The critics use long words to praise his books and urge people to buy them but hardly anybody does which means that except for family allowances we hardly ever have any money. We have rotas for sweets and ice cream and Fran and Ninian are more or less the only ones who ever get new clothes, the rest of us just go on covering up our nakedness with hand-downs and cast-offs.

It also meant that until we moved to Hallows Noon I had hardly ever ridden at all. I lived in a dream world where horses moved ghost-like at my side. I went to new schools riding an Arab stallion who moved wind-fleet beneath me, when strange children laughed at my father's ragged shirts and the way his black hair sprang out like flames from his thin, long-nosed face, or his habit of speaking aloud the words that overflowed in his imagination, the stallion would whinny gently and nudge me with his velvet soft muzzle. Then, instead of the jeering children, I would see the dark liquid eyes of my horse, the line of his fine-boned head and silken mane flowing over the crested arch of his neck.

Bay thoroughbreds, with coats that flashed white fire, lived in coalsheds and I exercised them over gallops tipped with ashes, tin cans, bedsteads and scrap metal, or I rode them all night over the lights and sleeping roofs of the city.

Ever since I had been old enough to know anything I had known that some day I would find the pony who was waiting for me somewhere. And then when I was nine the teacher from the primary school took a few of us home to see a programme on her colour television about life in a Tudor village. We were doing a project on Tudor life and she thought the programme would help us to make a better model of a Tudor village. We sat on the floor of her drawing room staring up at the screen. She switched it on and it flickered with a greenish light, became a dazzle of jagged lines which set into a picture of a grey horse being ridden by a tall, elegant woman. The woman sat in the saddle as if she grew out of it, she held her hands close to her body and there was only the slightest movement of her fingers as the grey horse cantered round the ring.

'Still the Horse of the Year Show,' said the teacher whose name I have forgotten, but who had a mole sprouting wire-strong hairs on her chin. She turned down the sound and stood in front of the screen asking us questions about Tudor manors.

I shut my eyes and saw the grey horse burning with the joy of its creation. I felt the supple saddle between my knees, the thin reins in my fingers, the proud neck and plumed mane reaching in front of me. The woman had gone, and it was me, Gillian Caridia, riding in the ring at Wembley.

When I told Mummy that some day I would ride in the Horse of the Year Show, that nothing could stop me, she said that she had felt like that about Daddy. She had seen him for the first time standing at a bus stop and she had known that nothing could stop her spending the rest of her life with him. She said that she believed me, that she was sure that one day I would ride and she went on patching the sleeve of Tor's jacket. Ninian said that if the fates decreed it I would ride, if not I would not, that I had no free will in the matter. Fran was the least hopeful. She said it was like ballet dancing, you had to start when you were an infant and I was too late already, but she sang Wild Goose for me to cheer me up.

At two of the places where we had lived I had got to know children who owned ponies. One girl was called June Dawlish and was fat and afraid. Her pony was an Exmoor called Trusty, which he wasn't. June was mean about letting me ride him, and most of the time I had to watch her riding and pretend that I knew enough about ponies to correct her mistakes. I taught myself to post and canter without stirrups on Trusty and I was just persuading June to let me start jumping when we moved on.

The other girl was called Mary Laird. She allowed me to exercise her bay pony, Socks, because she was too lazy to do it herself. I told her lies about all the riding I had done but still she would only let me ride round the roads and quite often her mother would chase after me in their car just to make sure that I wasn't doing anything else except walk.

Socks and Trusty were nice ponies but they weren't the ponies I dreamed of. Their heads were heavy and their beings were drawn down to the earth. Long ago they had accepted it as a fact of their existences that booted heels should drum endlessly against their sides and hands yank on their reins. In a way I didn't mind leaving them. I wouldn't reach Wembley on plodding, stubborn ponies.

So that we could afford to put down roots Daddy wrote a detective novel. He sat down at his desk and wrote it in four days and four nights, then he slept for two days and two nights. He typed it out in a fortnight and posted it to his agent.

'I have sold my soul,' he said.

'About time you sold something,' Mummy said. 'You owe it to your children.'

'Have you ever gone hungry?' demanded my father. 'Francesca, Libby, Tor, have you ever starved or even been hungry?'

'The real me is always starving,' said Fran, who never missed an opportunity. 'I have an untrained voice. If you'd written more detectives I could have had singing lessons.'

'Your voice is a cross,' said Daddy. 'I meant bread.'

'Never,' said Fran. 'I never touch the stuff. I'm going to slim.'

That night in bed she told me that she meant it. In the dark bedroom, the light shut out by heavy curtains because Libby couldn't sleep with them open, Fran admitted failure. She said with a quiet bitterness that she knew now that she would never be an opera singer.

'So that's why I must slim. If I can't sing in opera I'm going to be a pop singer.'

'You're not fat,' I said. 'And now Daddy has written a detective he may make thousands of pounds and be able to afford singing lessons for you.'

'It's too late,' said Fran. 'I must be skeletal thin. Thinner than you. I shall paint my eyes weird colours and grow my hair and wear white lipstick. Once I'm famous I shall sing like Eartha Kitt and wear gold dresses.'

'The old age pensioners won't like it,' I said.

'I shall still sing opera to them. They will headline it in the papers, "Francesca Caridia pop super star sings Carmen at charity concert".'

No one in our family ever really doubts their eventual fame and realizing that Fran had not abandoned her ambitions, merely let them veer a little, I said Goodnight and turning on my side I began to pray. As Catholics pray 'Hail Mary' and Hindus 'Hare Krishna' I prayed that I might ride at Wembley. With the warm sweet breath of Libby's brown hair in my nostrils I mouthed my petition over and over again.

'Please God forgive my sins and let me ride in the Horse of the Year Show for Thy son's sake.'

Next door Marc howled. I could hear the scratch of Daddy's restless writing as he struggled to capture on paper the words that would tell other people about the things that tortured him and Ninian argued with Mummy. I couldn't hear the words only the uneasy sound of their raised voices.

'Please God forgive my sins and let me ride at the Horse of the Year Show for Thy son's sake.'

Daddy's agent sold the detective novel straight away and it was published six months later. Daddy opened the parcel with his six free copies in it. They were piled in the green paper wrappings, one on top of the other. Daddy pushed them over with the back of his hand and they fell sprawling over the breakfast table. Six bulging blondes, six horrible head wounds dripping blood, six black titles warning death against pride and six Laurence Caridias written boldly across the jacket for all to read.

'I thought you were writing it under another name,' Mummy said in surprise.

'Then the lie would have been complete,' said Daddy, and he burnt the six copies of Death Be Not Proud in the kitchen fire, setting the chimney alight, rousing the local fire brigade and making us all late for school once again.

Two months later his agent sold the film rights and Daddy went to London to sign the contracts.

He was away for two days and when he came back it was after midnight and we were all asleep. Daddy's voice, shouting, woke me. Fran was already out of bed and running downstairs. Libby was sitting up at my side rubbing her eyes. I sprang out of bed and ran downstairs to join Ninian, Fran, Tor and Mummy.

'Wait till they're all here,' Daddy was saying as Una and Libby came stumbling down behind me.

'Attend directly,' he laughed, his arms round Mummy. 'All here?' and his eyes checked over us and I wondered suddenly if he was pleased to have us as a family or if we came between him and the things he really wanted in life.

'I have bought back Hallows Noon,' Daddy said.

We all gasped at the same time with sharp intakes of breath. If he had told us that he had bought Buckingham Palace we would have been less astounded. To us all Hallows Noon was Eldorado, Nirvana, somewhere over the rainbow, almost one of the many mansions that were being prepared for us. Even Mummy had never seen it. Daddy had grown up there with his two brothers who were killed in the war. Sometimes he would tell us stories about his childhood at Hallows Noon; about the land that had been theirs, the trees, the lake, the stables and the secret ways that only he and his brothers knew about. It was only when he had been drinking the treacherous amber whisky which made him remember all the buried things that he would tell us how his father died and the estate had to be sold to pay off the death duties.

'We will go back into our own again,' said my father. 'The Caridia family will live at Hallows Noon again.'

And we were all laughing and pushing round Daddy to ask questions, all talking at once. Only Mummy said nothing.

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans:

The Caridias: Gill, Fran, Tor, Ninian, Libby, Una, Marcus, Lawrence, Mrs Caridia: The Ramsays: Otta Ramsay, Mrs Ramsay, Sue, Jonathan, Mela Troughton

Equines:

Perdita, Tessy, Ruach, RIcky, Chenka, Davy Jones, Cuttle

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

The Fields of Praise (USA)

Series order

Series order