Jane Badger Books

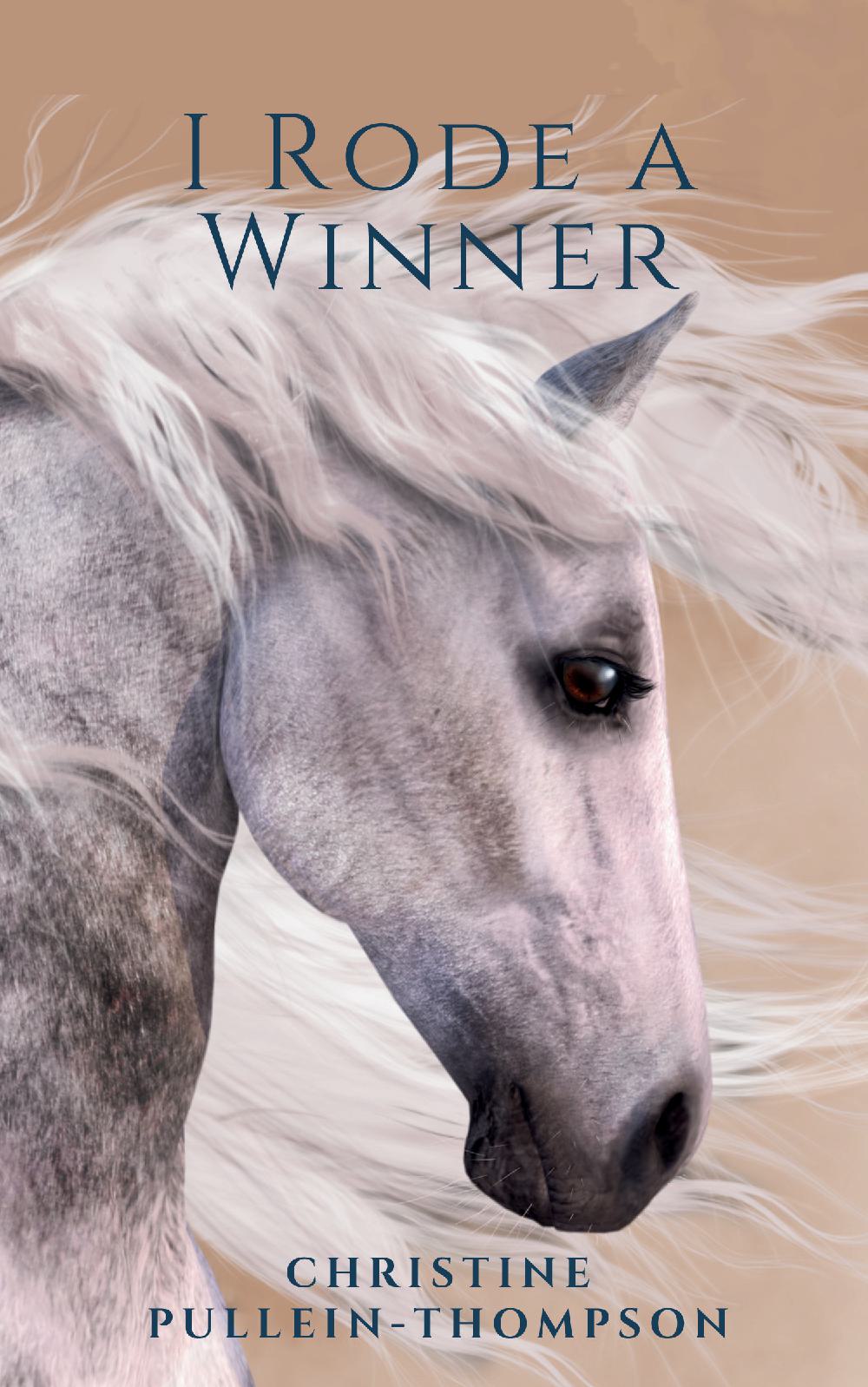

Christine Pullein-Thompson: I Rode a Winner (paperback)

Christine Pullein-Thompson: I Rode a Winner (paperback)

Illustrator:

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Debbie’s life is in turmoil. Her parents are divorcing: her father has already left to live with his new girlfriend, and Debbie is being sent to stay with her much older brother while her mother moves.

Simon runs a stable with his wife, Tina, and at first Debbie is appalled by just how much she does not know. She needs to be taught how to do everything: ride, muck out, groom …

Then Debbie finds she has a bond with Cleo, a grey mare no one else can ride. Slowly, Debbie and Cleo get better and better. To Debbie, Cleo becomes the one constant in a life that has nothing fixed about it at all. She is desperate to keep the mare, but after Simon has an accident the stables are in trouble, and Debbie finds herself, again, in a situation she cannot control.

Originally printed in the 1970s, I Rode a Winner is Christine Pullein-Thompson at her best, writing about a teenage girl trying to make her own way.

Page length: 130

Original publication date: 1973

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

IT isn’t easy to watch your parents part. I missed most of the rows, because I was sent to boarding school and when I returned they had already separated. I sat in my bedroom staring at my china horses. I didn’t see them because I was imagining my father leaving, banging the front door behind him, going without bothering to say goodbye to me, to leave a note explaining. It hurt. Then slowly tears came. Sometime later I was aware of my mother in the room, tall and beautiful, waving a letter.

“Simon wants to have you for the summer,” she said. “He says you’ll have to work for your living. But you don’t mind, do you? There are sixteen horses in at the moment and some others turned out.”

Simon is my brother. He failed most of his A levels and then, against everybody’s advice, married Tina. He had been riding for some time and Tina was already running a stable, so they simply moved into the stud groom’s cottage and ran it together. He’s years older than I am: I remembered him coming home from school, cursing like a trooper, playing his transistor full volume until the rest of the household reached screaming point.

“Do you think we’ll get on?” I asked now. “I mean we never did, did we?”

“He’s changed, mellowed. And Tina’s a sweety,” replied Mummy. “Anyway, there really isn’t anywhere else to go. We’re selling this house and I’m off tomorrow to stay in London and you know you would be bored there the whole holidays.”

I was pleased that I did not have to make up my mind.

“You can come to me, later, or stay with Daddy, whichever you like: I shall give you some money and Tina will help you get any clothes you may need—jeans, jodhpurs, etc. … You’ll have to learn to muck out and muck in,” said Mummy, laughing.

I remembered Tina at her wedding. She had arrived and left in a coach drawn by a four-in-hand.

“Daddy and I will be keeping in touch,” continued Mummy. “Daddy wants you for Easter and you’re definitely coming to me for Christmas.”

I started to feel like a parcel, something wrapped up in brown paper waiting to be posted somewhere for Christmas. I was trying not to cry again.

“You’ve always wanted to ride,” said Mummy, sounding guilty for the first time. “This is your big chance, darling.”

“Yes, I’m sure it will be fabulous,” I replied. “I shall enjoy every moment. I shall be a good worker and earn my keep.”

But I didn’t mean it for suddenly I wasn’t sure of anything any more. My whole life seemed to be toppling about my ears. I wanted Mummy to leave my room, but she lingered, picking things up and putting them down again.

“You will understand everything when you are older,” she said at last, putting an arm round my shoulder.

“I’m sure I will,” I replied, “even Daddy leaving without saying goodbye.”

“He’s writing to Simon’s place. Why don’t you change into a dress and we’ll go out and have tea somewhere,” said Mummy.

We lived in a town. My riding had been done during the summer holidays at a trekking centre in Wales. Outside the streets were full of people and we had to wait ages for tea. I kept biting my nails while Mummy made bright conversation.

Next day Simon came in a Land-Rover to pick me up. I hadn’t seen him for nearly a year and he had changed. He seemed much happier and he had left his transistor at home. His shoulders were wider too and his hair bleached yellow by the sun.

My cases were ready packed. I had put on slacks and a yellow shirt.

Mummy fussed over Simon and made him coffee in the kitchen which would soon belong to someone else. I stood on the pavement saying goodbye to everything. The garden was full of roses. A bird was washing himself in the bird bath on the lawn. I felt faintly sick.

Simon came outside at last. “Tina can’t wait for you to come,” he said, taking the two cases which held all my belongings. “She’s got rows of ponies lined up for you to ride. You’re going to have a wonderful time.”

He put the cases in the Land-Rover. I climbed in after them.

“I kept telling Debbie she’s in for a whale of a time,” said Mummy.

I wanted to leave at once. I hate partings and this one was even worse than usual. It was like parting from my whole childhood.

“We’ll look after her,” said Simon climbing into the Land-Rover.

Our house wasn’t a pretty house. It stood in a road where all the houses were supposed to be different—‘houses of character’, they were called—but somehow they all managed to have the same atmosphere inside. They were all middle class houses and all had lounges with cocktail cabinets, and coloured television installed, plus integral garages for two cars.

“I’ll write every day,” promised Mummy, while Simon started the Land-Rover. “And ring up tonight to see how you are, Debbie.”

I thought of someone else sleeping in my bedroom. “Goodbye,” I shouted without looking at anyone. “I shall be all right.” My voice had a croak in it. I looked straight ahead along the road and saw that the milkman was delivering milk and that the postman was late as usual.

“It’s best to get away,” said Simon after a time in an embarrassed voice. “I found that out quite soon.”

“But I’m younger than you were,” I said.

“You’ll like the ponies,” continued Simon, “and there are a couple of foals in the lower paddock. I hope to ride at Badminton next year.”

“You mean compete there?” I asked.

Simon nodded. “I shall probably break my neck, but one has to progress,” he said. “And then there’s the Olympics in three years’ time.”

He made everything seem possible. We were nearly out of the town now, green fields stretched into the distance.

“Surely you and Tina don’t look after all those horses on your own,” I said.

“Gosh no, there’s Derek; he’s our working pupil, you’ll like him, everyone does … then there’s Rosalind, Rosie for short. We all work very hard.”

“I’ve never mucked out, you’ll have to show me how,” I said.

I was feeling better—rather as though I had just woken up from a nightmare and found none of it was true after all.

“There’s some chocolate in that bag, help yourself,” said Simon, stopping at some traffic lights.

Another five minutes and we were in the country, driving through a valley with hills sprinkled with trees on each side.

“Only another thirty more miles,” said Simon. “How was school? Are you glad to be leaving?”

“I don’t know yet, some of it was fun,” I answered. “I expect I shall miss my friends.”

I found it difficult to keep my eyes open. I had hardly slept for two nights.

“It is better for people to part if they are unhappy,” said Simon. “You couldn’t expect our parents to stay together for another five years just because of you.”

“I know that. It just took me by surprise,” I answered.

The verges were white with meadowsweet. Cows stood sleepily in fields. Some time later Simon touched my shoulder.

“We are nearly there, just three more minutes,” he said, and I knew by his voice that he loved every inch of the road, and that this was home to him as nowhere had ever been before.

“There are the brood mares. Look! over there,” he cried. “Under the elms.”

I rubbed the sleep from my eyes and saw two ponies standing by a water trough.

“They’re called Nutmeg and Cinnamon,” Simon told me. “They’re ordinary ponies, but in foal to very good stallions.”

“When will they foal?”

“Next June.”

It seemed a long time away to me at that moment.

“Here we are,” said Simon, driving into a yard.

A crowd was waiting for us. “Welcome to Bullrock Stables,” they shouted.

“Come and be introduced,” said Simon, leaping out of the Land-Rover.

Rows of horses’ heads watched us over loose box doors. Two Jack Russell terriers yapped wildly with excitement and then threw themselves at Simon.

“Tina, Rosie and Derek, this is my sister Debbie,” announced Simon.

Rosie held out her hand.

“I’m glad you’re light,” said Tina, “you’ll be able to exercise some of the ponies. I had awful visions of you weighing ten stone.”

“I’m not much of a rider unfortunately,” I answered, shaking Rosie’s hand.

Tina was slim with long dark hair and blue eyes. She was well built with ruddy cheeks and a ready laugh. Derek had brown hair which didn’t lie flat and brown eyes. He was taller than I was, but not as tall as Simon who is six foot.

They all had a healthy look about them.

“Come on in,” said Tina. “Our place is small and untidy.”

Derek carried my cases. My bedroom was at the back. It was a small peaceful room with old-fashioned windows and walls more than a foot thick. The floor sloped and there was a beam across the middle of the ceiling which you had to duck under.

There was one large untidy sitting room downstairs, which you walked straight into, and a kitchen with a Raeburn cooker installed, and a larder. The bathroom was at the back, made out of the old wash house. Derek slept outside in a room adjoining the stables. The rooms all needed painting but the whole place was wonderfully comfortable with an atmosphere of peace about it.

“Do you want to telephone your mother?” asked Tina when she had shown me round, only omitting to show me Simon’s and her bedroom which she said was in a shambles and unfit to be seen by anyone, even relations.

“Perhaps I had better. Do I dial?” I asked.

“Yes, here’s the codebook,” replied Tina and then tactfully left the room.

I dialled home. Mummy was still there.

“I’ve arrived. I like it,” I said. “Are you all right?”

“I knew you’d love it,” replied Mummy cheerfully. “I’m just packing. The removal men are going to be here any moment.”

Our furniture was going into storage. I could see my face in a gilt framed mirror as I talked. My mouse-brown hair was tangled, my brown eyes were red from crying, my skin looked pale, my cheeks flabby. It wasn’t a face I liked at that moment.

“Well, be seeing you then,” I said.

“Here they are, I must go. Look after yourself,” said Mummy. “Don’t fall off.”

“Who are they?”

“The removal men.”

I didn’t want to say goodbye. I was suddenly homesick. I saw myself failing at everything, falling off the ponies, getting tonsillitis as I often did and then no one nursing me. I saw myself tongue-tied at lunch and miserable at supper and Tina and Simon becoming tired of me. I had never been a success at school; never a success at anything.

All this went through my mind as Mummy said, “Goodbye darling,” and hung up.

I looked round the room and wondered how long I would stay. I didn’t want any lunch but Tina made me eat.

“You can’t ride on any empty stomach,” she said.

“I’m no good at riding,” I answered.

“Don’t be absurd,” said Simon. “Of course you can ride.”

“I’ve caught up Heather for you. She belongs to an old lady called Mrs. Wells. She’s a very sensible pony,” said Tina. “She has to be exercised several times a week.”

“Or she gets laminitis,” added Derek.

“Laminitis?”

“Otherwise called pony gout,” replied Derek, leaving me none the wiser.

We ate mushroom omelettes with sauté potatoes, followed by ice cream.

“I have to take out Charlatan,” said Simon, leaving the table. “Will you lunge Dauntless, Derek? He needs about twenty-five minutes, a little longer on the near rein than the off.”

“And don’t forget that the blacksmith is coming at three to shoe Trampus and Rocket,” said Tina.

“I’ll wash up,” I offered. “I like being by myself and you seem to have a lot to do.”

“Rosie can manage the blacksmith,” said Simon over his shoulder as he left the room followed by Spick and Span. “But I want Trampus to have wedges behind, don’t forget now.”

I suppose to them it was just any other day, but to me it was like moving into a strange country. I didn’t talk their language nor was I like them. I was pale and indecisive. They were sunburnt and knew where they were going. They left the table with long strides. They didn’t hesitate or stop to wonder whether they were saying the right thing; even Derek at sixteen was self-assured.

“Don’t wash up. We’ll do it later,” said Tina, clearing the table. “Put on riding clothes and come and try Heather. Fresh air will do you good.”

I changed slowly, listening to Simon whistling as he led a chestnut horse out of a loose box and mounted him. He saw my face at the window and waved.

“Come and ride,” he yelled as though offering me a treat. “Don’t mope in the house all afternoon.”

I remembered him at home on long summer days, driving everyone mad, running away with my toys to hide them in the garden. I was five then and I hated him.

He had changed beyond all recognition. Perhaps I will change I thought, putting on my crash cap. Perhaps I’ll become a marvellous rider and surprise everyone.

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans: Debbie Ravenswood, Simon and Tina Ravenswood, Mrs Ravenswood, Mr Ravenswood, Derek, Rosie

Horses: Cleo, Charlatan, Mainspring, Heather

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order