Jane Badger Books

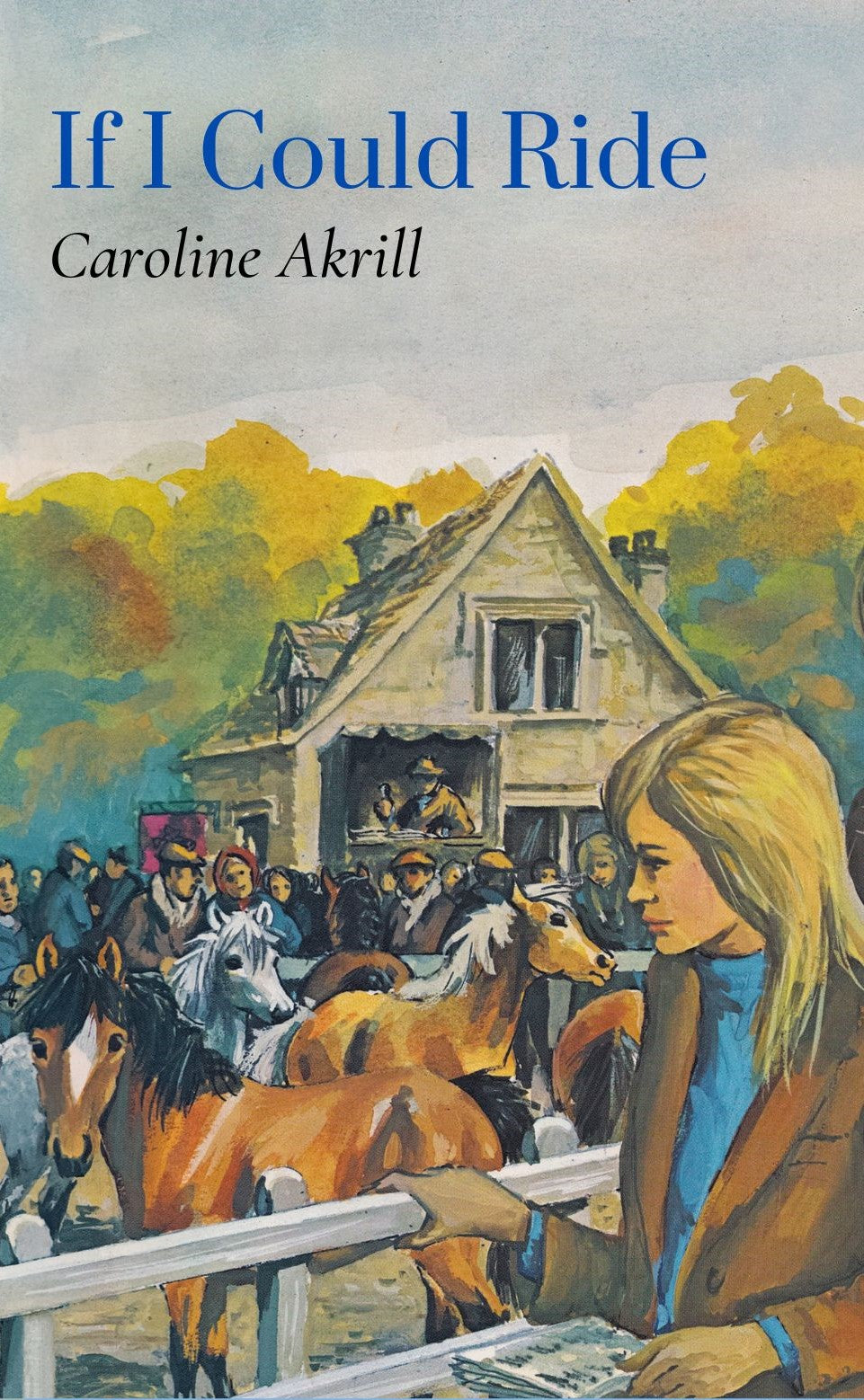

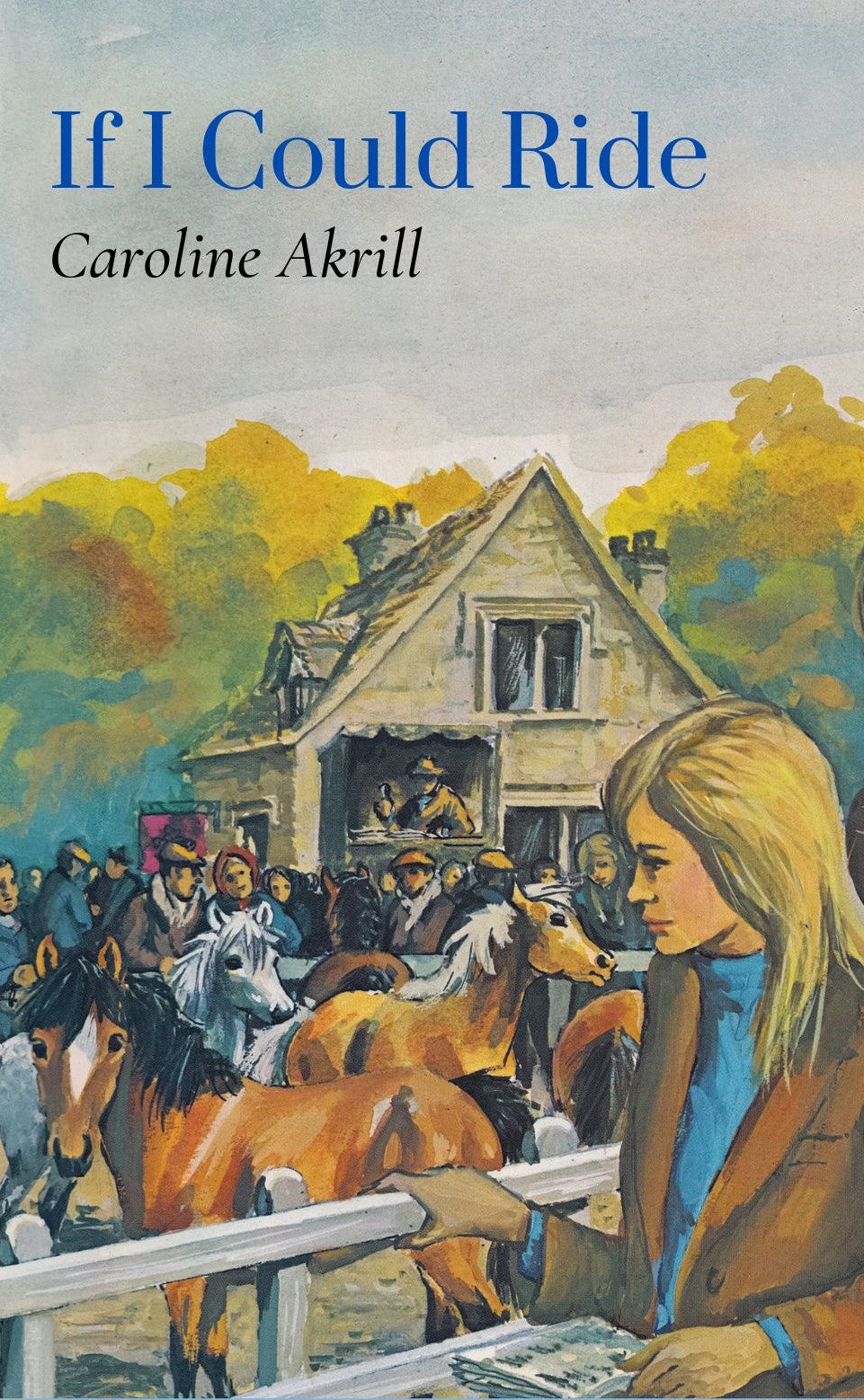

Caroline Akrill: If I Could Ride (paperback, Showing 3)

Caroline Akrill: If I Could Ride (paperback, Showing 3)

Illustrator: Elisabeth Grant

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

The best laid plans of mice and men …

Caroline has gone away to college to learn all about stud management.

It is not how she thought it would be. She cannot ride. All the horses at the centre are either brood mares or foals, who cannot be ridden.

In the middle of a lecture on parasite management, Caroline’s cousins ring up. They have their most spectacular plan yet in a career that has been big on spectacular plans, and they want Caroline to throw up her course and come and help.

If she could ride, thinks Caroline, surely it will all be worth it …

Showing 3

Page length: 138

Original publication date:

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

‘The Parasite is expelled on to the pasture as a second stage larvae, where it may remain in a dormant state for many weeks.’ Freda Farquhar paused to draw a little egg containing a coathook on the blackboard. ‘Has everyone looked at the slide under the microscope?’

‘If you examine a piece of bad banana,’ Debby said, her nostrils flaring at the thought of it, ‘it moves. It’s an absolute seething mass.’

Jilly stood up. She cleared her throat experimentally. She said, ‘The microbe is so very small, you cannot make him out at all, but many sanguine people hope, to see him through a microscope.’ She sat down with a bump. By way of explanation she added. ‘It’s Hilaire Belloc, you know.’

Freda Farquhar stiffened. She looked at us crossly. ‘We are not here to discuss bananas,’ she said. ‘Neither is the lesson about to develop into a poetry reading.’ In case of further doubt she wrote WORM CONTROL IN THE HORSE, in big letters on the blackboard.

At this precise moment, the telephone rang in the office next door. Because there was nobody in the office to answer it, it kept ringing, and because the hardboard partition between the two rooms was wafer thin, it interrupted worm control in the horse.

Freda Farquhar stood poised by the blackboard, hand arrested in mid-sweep. We who were her pupils stared at the little egg and the coathook until our eyes glazed. Eventually, and with a look of suffering, she laid down her chalk and went to answer the telephone.

As soon as she was out of the door, Jilly jumped up and pounded to the front of the class. She grabbed up the chalk and altered HORSE into HOUSE. She gave the coathook a nostril and two eyes. She was just giving the egg legs when Freda Farquhar came back. Jilly dived behind the blackboard.

‘It is most irritating to have to continually repeat one’s self,’ Freda Farquhar said, in a complaining tone. She stared at me indignantly and I nodded in agreement. Jilly took the opportunity to slip back into her place.

‘However,’ she continued sharply, ‘there appears to be someone in this class who is still unaware of the rule which forbids students to receive telephone calls before eight o’clock in the evening.’ Her gaze became more menacing.

‘It can’t be for me,’ I said. ‘No calls before eight o’clock. I know the rules.’

‘Except in the case of death, fire or famine,’ Debby said. ‘Flood, civil war, or similar Act of God.’ She turned round in her chair in order to look me over in a speculative manner, her eyes alert for potential drama.

‘I shall allow you to accept the call on this occasion,’ Freda Farquhar sighed. ‘But kindly be brief, and please advise your caller of our regulations.’

I promised that I would. I smiled in what I hoped was an encouraging manner because I could see that the lesson was sinking, if not already sunk. ‘If the discussion is not important,’ I said, ‘if the matter is not too pressing, provided that the issue is not crucial, then perhaps I will ask whoever it is to ring back after eight o’clock.’ But Freda Farquhar was glaring at the second stage larvae which had seemingly hatched in her absence.

Sarah’s voice spanned five counties. She said, ‘Are you happy? Will you stay?’

I opened my mouth to say I wasn’t happy; that studying for a diploma in stud work wasn’t at all as I had imagined it; that the acres of immaculate white-railed paddocks I had dreamed of hadn’t materialised, neither had the foals with their hand-knitted coats and their sweet breath smelling of milk powder and apples, and the brood mares with their dark and gentle eyes. Instead there were gateways awash with mud, there were bad-tempered animals who flattened their ears at your approach, there were rows of unspeakable preserved things in pickle jars along the window ledges, and there was Freda Farquhar. I wanted to say all these things, then I remembered the hardboard partition. I said, ‘I’m not allowed to talk until eight o’clock.’

‘That can’t be altogether true,’ Sarah said. ‘It isn’t a monastery.’

Becky shouted, ‘We rang for ages! We thought we would never get through!’

Simon took the receiver. ‘We want to know if you are happy,’ he said. ‘We have thought about it. We have discussed it, and we are not sure that you have done the right thing.’

‘Now you tell me,’ I said. ‘I can’t believe it. My ears must be deceiving me. I think you must be losing your reason. I think you must have forgotten that it was you who suggested I come here in the first place. It was your idea!’

‘She’s appalled,’ I heard Simon whisper to the others. ‘Horrified!’

‘Come home!’ Becky shouted.

‘There isn’t any riding,’ I said mournfully.

‘You knew there wouldn’t be,’ Simon said. ‘It was pointed out to you. “Studwork is all mares and foals and stallions,” we said. “There will be no riding.” You said you didn’t mind.’

‘I miss the riding,’ I said.

‘Does she hate it?’ Becky’s voice shrilled. ‘Is she complaining?’

‘You encouraged me,’ I said. ‘You said I should get some qualifications. Why, you even sent for the syllabus!’

‘There is no point in becoming hysterical,’ Simon said. ‘You may not realise it, but we are in an extremely difficult position.’

‘You are!’ In my anxiety I forgot about the partition. ‘What about me? What about the position that I’m in!’ There was a sharp rapping noise on the wall. ‘I shall have to go,’ I said hastily. ‘I am holding up the lesson.’

‘Curse the lesson,’ Simon said.

Sarah came back. ‘Things have changed for us,’ she said. ‘But we are pledged not to jeopardise your future. We agreed that we would ring only to ask if you were truly happy. If you are, we are not allowed to entice. We promised. We gave our word.’

‘We should never have promised not to tell,’ Simon complained. ‘How are we to explain? How can she possibly be expected to understand? It’s too bloody ridiculous.’

‘Swearing won’t help,’ Sarah said. ‘It really won’t. And do stop pushing, Becky!’

‘Tell me what you want me to do,’ I said. ‘Give me a clue at least. Explain the situation before I am expelled for talking out of hours. Don’t just waste time arguing amongst yourselves!’

‘Come home, Caroline,’ Simon said in an exasperated tone. ‘We need you.’

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans: Caroline, Simon, Sarah, Becky, Aunt Sybil, Mr Duffy, Mrs Carter, Adrian, Freda Farquhar, Mr Marmalade

Equines: Benjamin, seven tiny grey yearlings, the piebald cob, the liver chestnut gelding

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order

1. Caroline Canters Home

2. I'd Rather Not Gallop

3. If I Could Ride

4. Inside Pegasus