Jane Badger Books

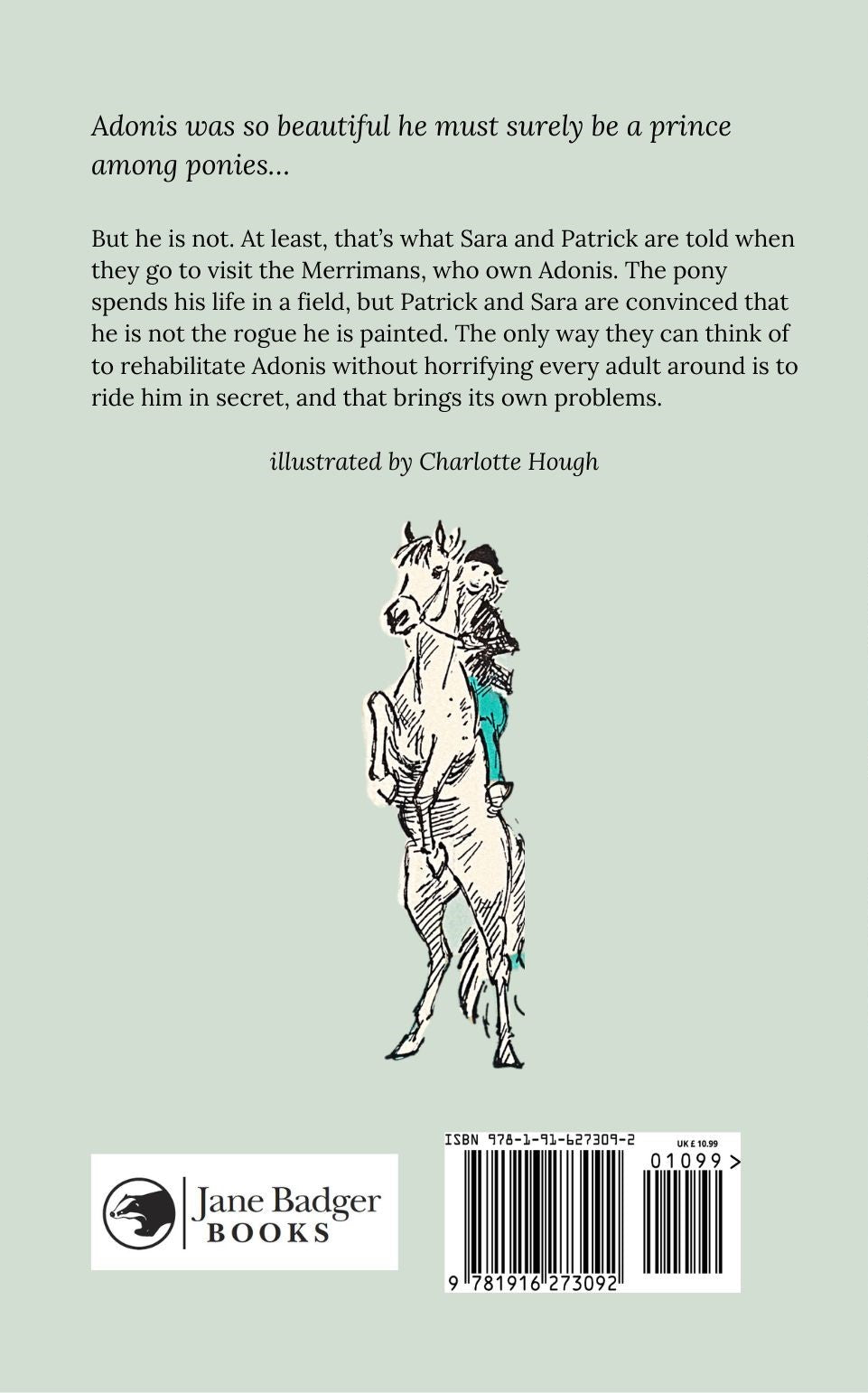

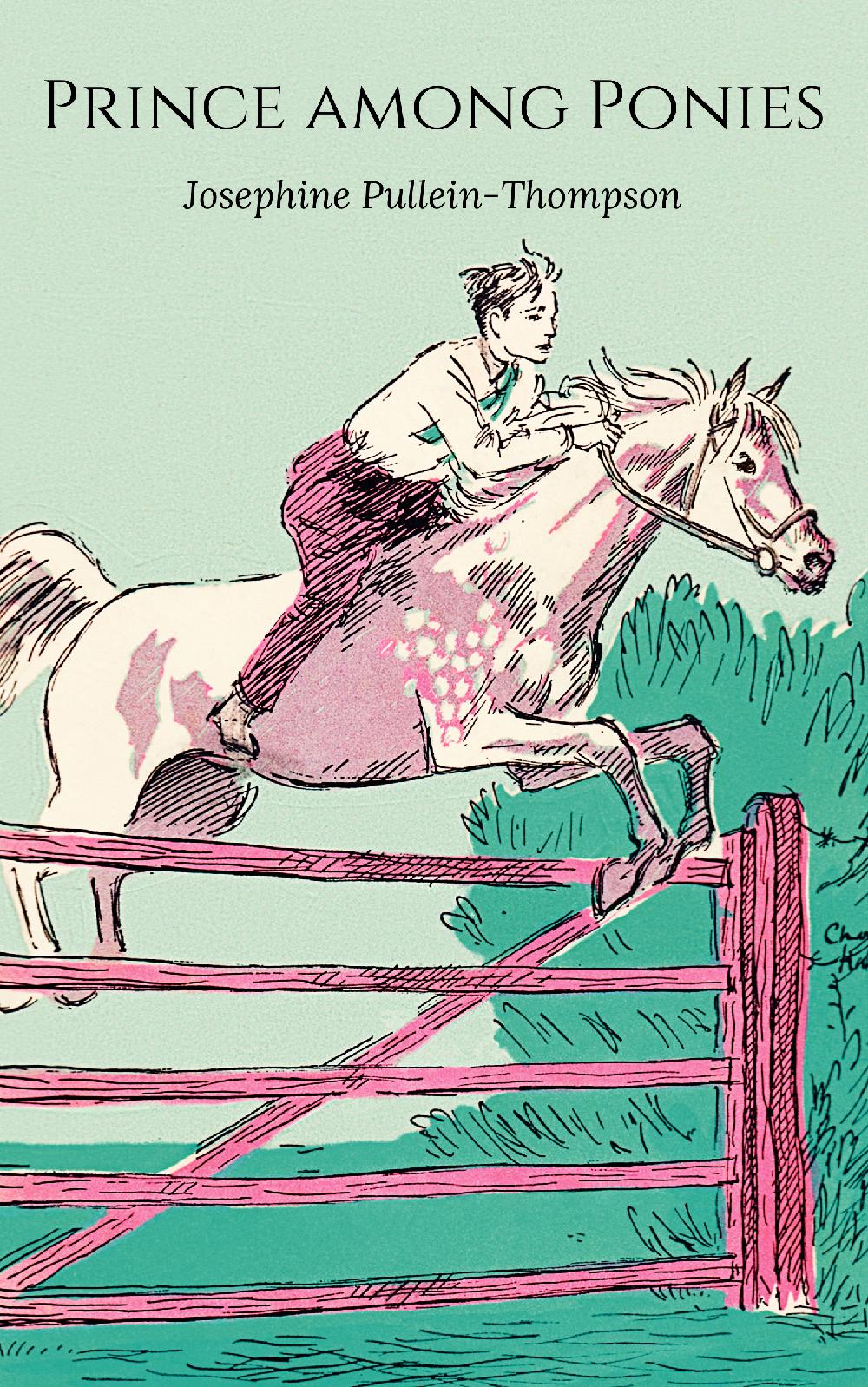

Josephine Pullein-Thompson: Prince among Ponies (paperback)

Josephine Pullein-Thompson: Prince among Ponies (paperback)

Illustrator: Charlotte Hough

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Adonis was so beautiful he must surely be a prince among ponies…

But he is not. At least, that’s what Sara and Patrick are told when they go to visit the Merrimans, who own Adonis. The pony spends his life in a field, but Patrick and Sara are convinced that he is not the rogue he is painted. The only way they can think of to rehabilitate Adonis without horrifying every adult around is to ride him in secret, and that brings its own problems.

Page length: 202

Original publication date: 1952

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

The worst thing in the world is to have unhorsy parents.

Patrick, my elder brother, says that this is a sweeping statement, but I think that it is a Great Truth.

Our parents, though nice and perfectly reasonable in all other ways, were not only unhorsy, but positively anti-horse. In some way that Patrick and I could never fathom, this anti-horse complex was mixed up with our Great Uncle Harry. In our very young days, when Black Beauty was the only horse book which we had read, we came to the conclusion that Uncle Harry had been killed in the hunting field. Patrick was convinced that he had broken his neck while jumping a brook. But as we grew older and learned that people don’t break their necks as often as Black Beauty’s mother thought, we dismissed this idea, but we were no nearer solving the mystery of our parents’ unhorsiness.

The older we grew, the more horsy we became. We played horses, harnessing each other to my dolls’ pram, and then we each had an imaginary horse which we rode everywhere. Mine was a well-bred, fidgety chestnut mare called Firefly, and Patrick’s Demon was a fiery black stallion with a flowing mane.

It used to make Mummy rather cross when she observed by our actions that we were riding down Bond Street on our lively steeds. Demon and Firefly always behaved in a dramatic manner; they were very badly schooled and I don’t think they ever walked a step. If they weren’t dancing and prancing they were rearing, bucking or bolting.

Our parents soon gave up asking us what we would like for our Christmas or birthday presents because we always asked for ponies or riding lessons, but then, one Christmas a year and a half before the beginning of this book, to our amazement and joy we were each given a riding outfit and two dozen lessons.

“To get this nonsense out of your systems,” Daddy said. And Mummy added, “They won’t be so keen when they’ve fallen off once or twice.”

Marston Common, where we live, is a suburb just outside London; it is our second misfortune, for Patrick and I would like to live in the country.

While we live among the pavements and shops, the thousands of squashed-up houses and millions of people, we long for a cottage in the country, miles from anywhere, with stabling for six and several nice big fields.

However, Marston has two good points: one is the Common and the other the three riding stables. Two of the riding stables are very superior establishments, but the third hires out thin horses to people who can’t ride. Our parents had booked our lessons at Captain Stefinski’s stable, which is the most superior of all.

“We may as well do the thing properly,” Daddy said, “and I’m told Stefinski’s one of the best instructors in the country so we can’t go wrong there.”

Patrick and I rode in the covered school on Copper and Silver or hacked across Marston Common and into Sackville Park on Treasure and Jonathan, and each week we became even more keen on riding. Our parents were horrified; especially when Captain Stefinski told them that we were very promising. I don’t think that anyone had ever thought us promising at anything before. We had just started to learn to jump when our two dozen lessons came to an end. We had hoped that when our parents found our horsiness was too deep rooted to wear off they would relent and let us continue our lessons. To our dismay they refused to discuss the matter; they said that we couldn’t do everything and that we were going to have tennis coaching instead. Against our wills we were provided with new and very super racquets, which were the envy of our friends, elegant white outfits and one of the best tennis coaches in London. Patrick did not mind terribly because he likes tennis, but he said it was a waste of money as he would never be good, and that he should think we could have had a riding lesson every week for a year on the money the parents had spent on dressing us as though we were going to play at Wimbledon.

It was much worse for me. I’m no good at all at games; I hated every minute of my coaching and so did the coach. When I stood on the hard court and tried to develop a non-existent backhand I thought of Captain Stefinski’s covered school and Copper, and when I played on grass courts I thought of the canters we had had across Marston Common; uphill to the lonely pine and alongside the sandbanks. When we were taken to watch the play on the Centre Court at Wimbledon I fidgeted in my smart seat and longed to be sitting on the grass at the humblest horse show in England.

Patrick remained optimistic; he said that when autumn came and our parents’ craze for tennis wore off we would be allowed to ride again. But he was wrong. Autumn brought squash lessons for him and dancing lessons for me. In the Christmas holidays we learned to skate on the big indoor ice-rink at Sanford. It was fun, but not as exciting as jumping. Patrick, at last becoming as frantic as I was, announced that he was going to spend the money he had been given, as Christmas presents, on riding lessons. This was not at all well received; in fact he was forbidden to do so, and we were both lectured on the evils of one track minds and horse bores and on the virtues of being good “all rounders.” As Patrick said to me afterwards we were rapidly becoming bad “all rounders”.

To cure our one track minds we were taken to nearly every Museum in London, and they all made my legs ache. When we weren’t at museums we were at pantomimes, which we used to like when we were little, but which increasing old age made us hate.

Spring came, but we didn’t dare mention riding. Patrick was provided with a cricket coach and I was made to take up eurhythmics, which were ghastly and a hundred times worse than dancing. It wasn’t until the summer term that a gleam of hope appeared on the horizon.

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Human: Sara, Patrick and Mrs Huntingdon; The Merrimans (Mr and Mrs Merriman, Michael, Celia, Jane, Geoffrey) Captain Stefinski

Equine: Adonis, Druid, Warrior, Rupert, Thunder, Starry, Christmas, Billy

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order

Loved this story as I have always loved Arabs particularly Grey's. The book reminded m of my experiences as a teenager with horses and the joy of riding a brave and spirited horse. Beautiful book so pleased I'm able to read it and own the copy. Thankyou for republishing g these lovely stories

Wonderful book! Loved reading it as a child - loved reading it again as an adult