Jane Badger Books

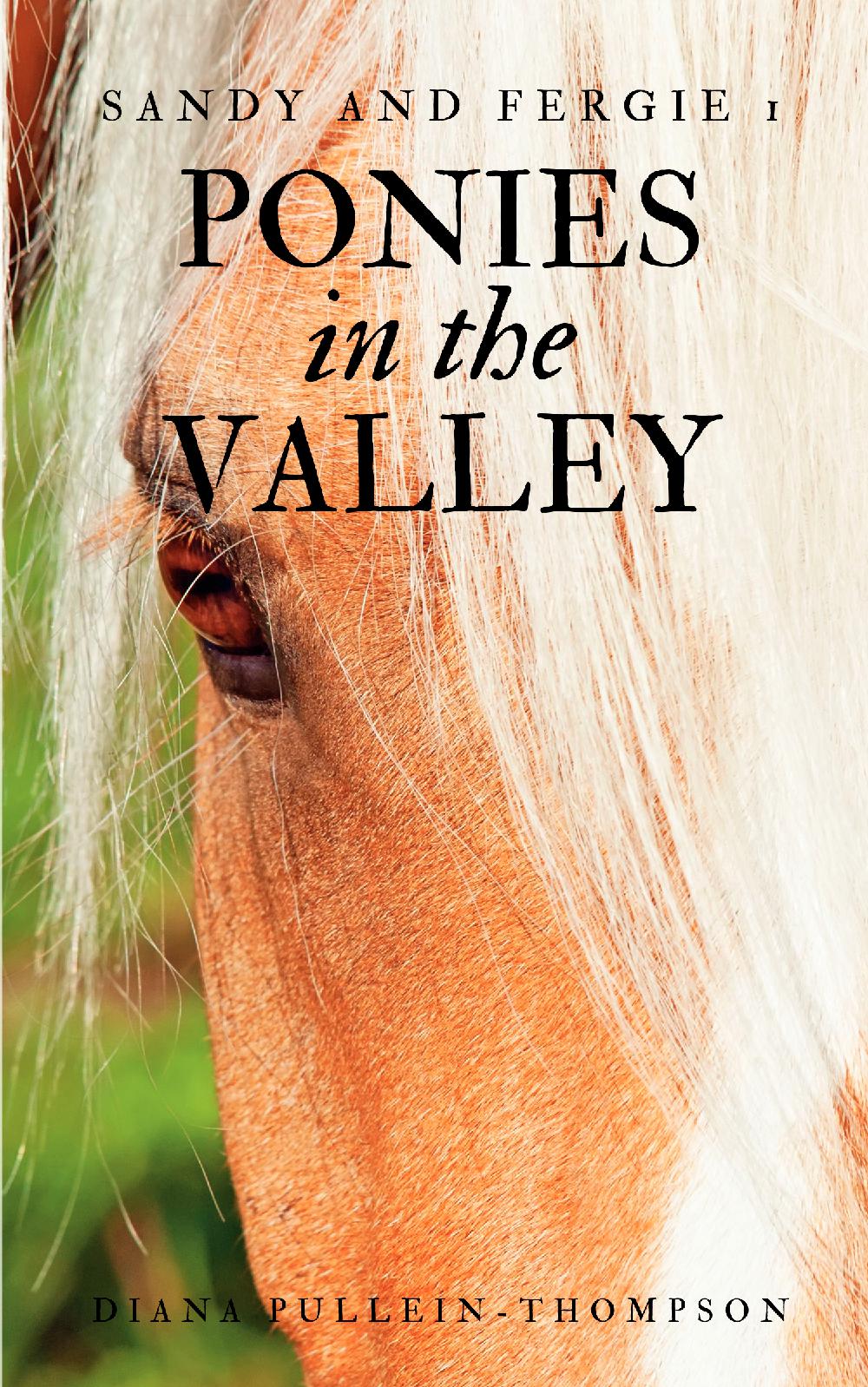

Diana Pullein-Thompson: Ponies in the Valley (paperback)

Diana Pullein-Thompson: Ponies in the Valley (paperback)

Illustrator: None

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Sandy and Fergus are moving to the country, but the whole family face difficulties they hadn't imagined. Their father is recovering from a heart attack, and Sandy and Fergus manage to offend the local children. But they do have a pony, something they've longed for all their lives. Mimosa is beautiful: a palomino Welsh cross, but she has a mind of her own, and neither Sandy nor Fergus know enough to stop her.

Published in the 1970s this series is a much more realistic one than Diana's earlier series of the 1940s and 1950s. Sandy stops eating beef when she becomes fond of the cattle her father keeps. She has very mixed feelings about hunting. There are people with difficult family backgrounds, and a thoroughly realistic outcome to the children's greatest adventure, when they try and stop rustlers stealing their animals.

Sandy and Fergus 1

Page length: 148

Original publication date: 1976

When will I get my book?

When will I get my book?

Paperbacks are printed specially for you and sent out from our printer. They are on a 72-hour turnaround from order to being sent out. Actual delivery dates will vary depending on the shipping method you choose.

Read a sample

Read a sample

Do you know what it is like to long so much for a pony you are jealous every time you see in the paper a picture of a child riding?

Well, that is how it was with me. The wanting started I was eight, three years before this story begins. I was tubby then, sandy-haired and ludicrous. And nobody took much notice of me—or that is how it felt. My parents said I was going through a phase which would pass; it was all a natural part of growing up, nothing odd about it. Girls often fell in love with ponies and switched to boys when they were teenagers. They obligingly gave me china and wooden horses for my bedroom’s radiator shelf for birthdays and Christmas, stuffed my Christmas stocking with paperback pony books, and let me stay up late to watch show jumping on the telly.

And when we went on holiday in Wales, they sent me pony-trekking with a packet of sandwiches. But none of this made up for not having a pony of my own. It couldn’t compensate completely.

Fortunately, I was not alone. My brother, dark-haired, Celtic-faced Fergus, shared my longing. Wanting a pony was the one thing we had in common. Our parents had a theory about Fergus, too. His longing, they said, was due to his love for adventure, his boyish nature thrilling to the sensation of speed. He wanted to gallop with a keen wind in his face, like the cowboys he watched so avidly on television. But they were wrong. Fergus wanted, also, to care for a pony, to brush its mane and tail, to feel its hot breath on his neck as he oiled its hoofs. To hear its welcoming neigh of a morning and feel “this is ours, our very own”. Parents do not always understand that there is a world of difference between hiring or borrowing something and owning it. When you know something is yours you feel safe because nobody can take it away.

For a time we had ridden at a rather formal riding school outside Sonnywood. We had walked, trotted and cantered over and over again in a covered school, while a fat, dark girl stood in the middle beating her booted legs with a riding whip, while she told us for the hundredth time to sit down in our saddles or to keep our toes up and stop waving our arms around. It was not the sort of establishment where the pupils groomed or saddled their mounts. When the ride was over it was, “Goodbye, see you next week”, and that was that. You were off pretty sharp, with barely a backward glance at Celandine or Dawn or whoever you had ridden. After a year, Fergus had found this kind of riding a drag and, to my parents’ disappointment, had given up. His jodhpurs and crash cap went to the “Good As New” shop, and riding became another sport, among many, which he had started and given up. I carried on for another six months and then followed suit, but my parents kept my clothes for me... in case I wanted to continue pony-trekking.

Until I was eleven we lived in a cul-de-sac, green with conifers but bare in hedges, the front gardens being open-plan. Our house was built of yellow brick, on the ground floor and then of concrete blocks, faced with white timber, on the first. It had modern windows which opened out horizontally, and this meant you could never put your elbows on the ledge and yell to your friends passing down the street, for if you did the top of the window hit you on the head. Built into the house was a spacious garage for three cars with standing space outside for another. At the bottom of our small back garden traffic hissed, spat, purred or roared along a busy road.

Sonnywood has more cars per head of population than any other town in Britain. Cars are made there and sent to many parts of the world. There was a car factory just over a mile from our house, which, when this story begins, was being extended. People talk cars in Sonnywood, they think cars, and I believe they dream of cars too, so many of their livelihoods depend on cars. I hate cars, of course; they are stuffy to ride in, dreary to look at, noisy, smelly and anti-social. I think cars are spoiling the world. My parents said we could have had a pony each, but for the danger from traffic. There was, they pointed out, nowhere safe to ride for miles around. There was only one bridle path in Sonnywood, just half a mile long, but four golf courses taking up hundreds of acres.

It was deadly dull, although I didn’t realise how dull until I left. I think I hated the golf courses most of all, because I could picture myself galloping across them on the dappled grey mare of my dreams. I saw myself leaping up and over the bunkers as though they were Irish banks and circling on the greens, and always the sun was shining and the southern wind was soft on my cheek and my pony—Silver, Snow Cloud or Mimosa, I never settled on a name—was going beautifully with arched neck, relaxed jaw and action low and swift.

Fergus and I went to smart and expensive private schools, where we were well taught by mostly pleasant people. Fergus played rugby vigorously, took up judo and went to Edgbaston County Cricket Ground for coaching. I played netball and hockey fairly badly, belonged to the local swimming club and took up music.

Every evening on school days, after finishing our prep, we watched television. In the holidays and at weekends we played in the back gardens in the cul-de-sac with our friends Emily, Peter, Jo and Ben.

We were not unhappy, for we did not know what we were missing, apart from a pony. We were simply bored, and so well protected from the dangers of Sonnywood that sometimes we felt caged. Our parents considered the roads too dangerous for bicycling as well as riding, so, although we had bikes, we could only whizz up and down the cul-de-sac on them. So Fergie (I shall stop calling him Fergus now—only our aunts call him that—became interested in cars, because everyone else was, and when Mummy was out he used to drive her Mini in and out of the garage). Once in a moment of acute boredom he took it round the cul-de-sac and back, which was quite a daring thing to do. He came back with a smile like a gash in an apple across his face. But a neighbour had seen him and that night when Dad returned, there was hell to pay, no pocket money for a month, one hundred lines to write and a long lecture from Dad, who is sandy-haired with a wide, bland face and eyes almost scilla-blue.

I’m like Dad—in looks, I mean. Our parents, thinking I would take after Mummy, who is dark-haired with a high Scottish brow and the air of a lady about her—in keeping with her Scottish name, Hugheena—called me Alexandria. But I haven’t the dignity for such a stately name, and my casual manners, round bouncy sort of face and thatch of straw-coloured hair soon led me to being called Sandy. And that’s how I see myself, a Sandy, not an Alexandria.

Fergie is very different, dark with sensitive coffee-coloured eyes in a sharp face with Mummy’s brow. He’s taut as wire stretched to the limit. One day I think something will snap and his face will crumple. But we complement each other pretty well and we don’t quarrel much.

The first sign of approaching trouble was when our parents stopped going to their Bridge Club on Wednesdays. This upset us slightly because we missed June, our childminder, who came on those evenings and allowed us to watch television almost until it closed down for the night. June’s handbag always seemed full of sweets and she used to make us cups of steaming hot chocolate to take up to bed. She was very fat, with legs like sausages, but naturally we liked her because of the chocolate, the sweets and the late television, and also because she had a fat gurgling laugh which made us giggle, and she was never, never cross. We felt she was on our side.

The next sign of disaster appeared like an ugly jack out of a box one grey March day when Mummy said: “We shan’t have the Rover after tomorrow. Dad’s leaving his job. He’s redundant.”

“Got the sack?” asked Fergie, incredulously.

We were sitting in our fully fitted kitchen, which had a picture window looking across our ornamental back garden, eating shop ice-cream at the breakfast bar, while Mummy opened a tin of soup for Dad’s supper. A plane droned lazily overhead. A bird in the flowering cherry sang a chilly, evening song. A little rain ran like beads of mercury down the double-glazing.

“Not sacked. Redundant. There’s a difference.” Mummy’s lips were tight and her brown eyes did not glance in our direction.

“Can’t he get another job?” asked Fergie, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand, which he is not allowed to do. “The newspaper is full of advertisements for … accountants, solicitors, that sort of thing.”

“But your father isn’t that sort of thing, is he?”

“Shall we be poor?” I asked, seeing a tiny cottage, two-up, two-down, a loo out back, bread and marge for tea, my toes peeping out of my plimsolls. “Perhaps we could live in Wales.”

“Now you are being ridiculous. Wales has one of the worst unemployment problems in the country. Please stop trying to be clever. I just wanted you to know about the Rover, in case you asked your father where it was.”

No hope of a pony now, I thought. No hope at all.

“Poor Dad!” I said.

“Your father keeps on trying, but he’s forty-four—that’s a bad age for starting anew. I may go back to teaching. I don’t know. The trouble is, your school fees come to eight hundred a year, with all the extras.”

She turned on the sink disposal unit to churn the potato peelings into pulp.

“Enough for two ponies,” I muttered.

“Shall I have to leave Hunter’s Wood?” asked Fergie.

“Maybe.”

“I don’t mind,” he lied. “I’m older now. I shall do all right at the other place. Please don’t worry about me.”

Fergie had tried the state school and failed. The sheer size of the place had overwhelmed him when he was seven, and his self-confidence had dwindled. He had been put in the stream above remedial—the C stream—and sat at the back of a class of forty and learned very little. He couldn’t read more than the easiest books at nine, so, as their status improved, my parents had taken him away and sent him to Hunter’s Wood, which had only ninety-eight children and classes of around twenty. There he had flourished. But now my mind was not on school.

“Shall we move?” I asked, the cottage still in sight with a paddock studded with buttercups, graced with two ponies.

“Maybe, maybe. We must wait a wee while. Nothing is certain. He’s trying for something in market research today.” She turned to face us at last, very dignified, rather beautiful, not a line of anxiety in her face. Her dark hair grows up from a widow’s peak to crown straight features. Her nose is short and elegant with a prominent bone in it. I think her face is very Scottish, not the raw-boned muckle-mouthed sandy-haired variety, but the stern Celtic kind.

Fergie stood up, took her hand and gave it a little squeeze, which was really rather charming of him.

“Never mind,” he said.

Who's in the book?

Who's in the book?

Humans: Sandy, Fergus, their parents, Jake, Steve Trevor

Equines: Mimosa, Jasmin

Other titles published as:

Other titles published as:

Series order

Series order

1. Ponies in the Valley

2. Ponies on the Trail

3. Ponies in Peril